Abstract

This article presents a new approach to the socialist calculation debate. I focus particularly on the question of how to integrate information of consumers’s preferences and argue that the objections raised by Austrian economists against the socialist model proposed by Oskar Lange can be addressed within the current level of technological development. I propose that preferences of consumers can be revealed by their web search queries and also that, given the amount of information available, it would be possible to analyze consumers’s preferences in terms of hierarchical choices that distinguish between needs and subneeds.

Keywords: Cybersocialism, socialist calculation debate, web search queries JEL Codes: B5, C6, P2

Introduction

Marx envisaged a socialist society but he gave very few clues about how it would function in the practice. Since then the question of the building of Socialism has remained as an open issue, although important efforts have been made into that direction. One work that deserves particular attention is that of Oskar Lange (1938) who, “in a truly Marxist tradition, since it envisages the advent of Socialism in a mature Capitalist market economy” (Desai, 2014: 154), proposed a model for a socialist economy. His work was mainly objected by Austrian economists, whose critiques referred mainly to questions of computability and information regarding consumers’s preferences. In this text I argue that these objections can be addressed within the current level of technological development, which would bring conditions for the emergence of cybersocialism. Perhaps I should start by clarifying what I mean by cybersocialism: a socialist society where cybernetics is the medium that coordinates the different processes of the socialist economy. This definition is based on Oskar Lange’s original works. In his Introduction to Economic Cybernetics, he states that

the systems with which cybernetics deals are collections of elements connected with one another by a chain of cause-effect relations. This sort of relationship among the elements of a system is called coupling. Hence cybernetics may be defined as a science of the functioning of the system of coupled operations. For a socialist economy cybernetics is of particular importance. In the socialist socio-economic system, similarly as in any other system, we are dealing with a set of operations of a large number of elements (in the final analysis these elements are particular individuals) but in a socialist planned economy, in order to achieve a desired result, these elements can be collected, sorted and combined into appropriately coupled systems. Socialism sets as a basic task the possibility of managing the socio-economic processes which in a capitalist economy develop spontaneously. This explains the fact that the general theory of the functioning and management of systems of coupled operations is of great importance in socialism (Lange, 1970: 6).

The paper is organized as follows. The first section focuses on the works of Enrico Barone and Ludwig von Mises, which sparked off the debate about economic calculation under socialism. In the second section I present the response given by Oskar Lange, where he proposed a socialist economy organized by a trial-and-error rule. The third section discusses the main objection addressed against Lange. In section four I argue that the problem identified in Lange’s work by von Mises about the incomplete information regarding consumers’s preferences can be addressed through the use of web search engines. Section five concludes the paper with final thoughts. It is important to point out that this paper does not deal with the question of the computational power required to process all the information. In Cottrell and Cockshott (1993, 1993a) this point is discussed in detail.

Socialist calculation debate: first arguments

Before discussing the socialist model proposed by Oskar Lange, it is worth introducing the work by Enrico Barone, whose essay “The ministry of production in the collectivist state” was the starting point for the debate about the possibility of optimal allocation of resources in a socialist economy. In this seminal paper written in 1908, Barone shows that the equilibrium point reached in a socialist economy is mathematically equivalent to the one resulting from a competitive market system. In both cases, socialist and capitalist economies solved the same set of equations although through different mechanisms. Given the fact that there are no prices in the socialist economy, the Ministry of Production allocates the resources utilizing indicators of exchange:

(…) some method of determining ratios of equivalence between the various services and between various products and between products and services. Individuals bring their products to the socialized shops to exchange them for consumables or state owned resources for own use.

Twelve years later, the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises stated the impossibility of reaching an optimal allocation of resources in a socialist economy. Marxist economists Cottrell and Cockshott suggest that for Mises this impossibility was not logical: what he believed was that “there was no practical way of realizing” rational calculation under socialism (Cottrell and Cockshott, 1993: 4). In a later essay, Hayek clarified this point. The problem with a socialist economy was not about its theoretical fundaments, but about the huge amount of information that it had to process in order to achieve an optimal result. Hayek stated that a socialist planner needed to solve thousands of equations, which was not only unpractical but also inefficient because the market mechanism can solve the same equations without needing someone to do so.

The socialist economy of Oskar Lange

The next step in the socialist calculation debate was taken by Oskar Lange in his opus “On the economic theory of socialism” (Lange, 1938), which was based on the idea that “socialism can easily imitate the efficiency of market capitalism if the central planning board is able to supplant the Walrasian tâtonnement process” (Auerbach and Sotiropoulos, 2014: 219). Lange proposed an economy with a socialist planner who, through a mechanism of trial and error, would emulate the functioning of market processes with private property more efficiently. In this socialist economy there are no prices in the conventional sense of the word, i.e. as the exchange ratio of two commodities, but they appear as mere indicators of available alternatives.

In such an economy, there is no market for capital goods and productive resources. The only markets are those for labor and consumer goods. The absence of market for capital goods implies that there is no price for capital and, as a result, the maximization of profits no longer makes sense in this model. Thus, managers’s efforts are not oriented by this maximization condition. Instead, the central planning bureau instructs the managers to minimize the average cost of production and also to produce until the point where the marginal cost (i.e. the cost of producing one additional unit of product) matches the price. It is in this point where the process of trial and error enters:

Starting with an arbitrary set of prices, the price is raised whenever demand exceeds supply and lowered whenever the opposite is the case. Through such a process of tâtonnements, first described by Walras, the final equilibrium prices are gradually reached. These are the prices satisfying the system of simultaneous equations [of this socialist economy]. It was assumed without question that the tâtonnement process in fact converges to the system of equilibrium prices (Lange, 1967: 158).

The conditions established by the central planning bureau (minimization of the average cost of production and the equalization of marginal costs and prices), in conjunction with the convergence of the process of trial and error towards a system of equilibrium prices, guaranteed that the solution achieved by the central planning bureau is, at least, as efficient as the solution reached through conventional market processes.

Austrian objection to Lange’s model: incomplete specification of consumer demand functions

In Enrico Barone’s pioneer work, discussed in the first section, it was assumed that the central planner had complete knowledge of the consumers’s preferences. This assumption was retained by Lange, who believed that the central planning bureau was able to correctly calculate the gradation of the values of consumers’s goods. This assumption is key, because consumers’s preferences are necessary to compute the consumer demand functions, which in turn are utilized in the trial and error process. First Mises, and then Hayek, objected that this assumption was unrealistic because it is only through market processes that the true consumers’s preferences can be revealed. As Mises explains,

for a utilization of the equations describing the state of equilibrium, a knowledge of the gradation of the values of consumers’s goods in this state of equilibrium is required. This gradation is one of the elements of these equations assumed as known. Yet the director knows only his present valuations, not also his valuations under the hypothetical state of equilibrium (Mises, 1949: 707).

In the case of a market economy, the gradation of the values of consumers’s goods manifests itself in the free exchanges. Every transaction generates new data that are processed by the market, which results in a continuous process of information dissemination. In this sense, building on Mises, Hayek states that

(…) the data from which the economic calculus starts are never for the whole society given to a single mind which could work out the implications, and can never be so give (…) The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess (Hayek, 1945: 520).

In the next section I argue that this problem can be solved with the current level of technological development. Prices, understood by Austrians as channels of information of consumers’s preferences, are redundant in an environment where information is everywhere.

Counter-argument: the equivalence relation between web search queries and consumers’s preferences

In this section I argue that the current level of technological and computational development allows the central planning bureau to know what the consumers’s preferences are. From the Austrian point of view, the main problem faced by Socialism was the difficulty of collecting all the relevant information regarding consumers’s valuations. While this standpoint was accurate in the past – particularly in the USSR –, the situation has completely changed in the present. The development of software systems designed to search for information on the World Wide Web – known as web search engines – gives us the possibility of processing and ranking information. Through mine data available in databases, today it is feasible to track searches and to dive deep into users’s interests.

Thus, the building block of my proposal is the idea that there is an equivalence relation between web search queries and consumers’s preferences.1 In a paper written by Paul Samuelson in 1938, he proposed his revealed preference theory, where he states that preferences of consumers can be revealed by their purchasing habits. The key point in his theory was the following: if the consumer buys good A over good B, where both goods are affordable, it is revealed that he directly prefers good A over good B. In our case, what I propose is that preferences of consumers can be revealed by their web search queries.2

With the amount of information available, it would even be possible to analyze consumers’s preferences in terms of hierarchical choices that distinguish between needs and subneeds. In a market economy this distinction is irrelevant; however, in a socialist economy, the identification of this hierarchy of needs helps the central planning bureau to find workable rules for its process of decision making.

Thus, the critique made by Mises and Hayek regarding the impossibility of integrating dispersed information can now be solved. With the current level of technological development, the socialist economy posed by Oskar Lange would have the required conditions for its functioning. What the central planning bureau requires to do is to transform the web search queries into consumers’s preferences. In the next paragraphs I show real examples of how these searches are in fact an expression of web users’s preferences.

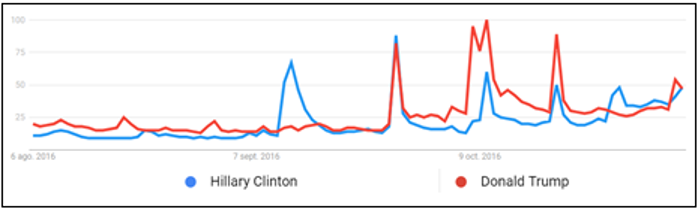

The first case comes not from the economy but from politics. There are several historical examples where surveys failed in identifying the winner of an election. The most recent case is the U.S. election, where there was almost a consensus around the imminent victory of Hillary Clinton. Most of the polls assured by a wide margin that people preferred Clinton over Trump. However, as we know, the final outcome in terms of the number of votes was practically a tie, a 50-50 result. The theory of preference falsification (Kuran, 1995) has an answer for this puzzle. What happened was that in highly controversial contexts, such as the 2016 U.S. election, people prefer to hide their true preference in order to avoid conflicts. However, in search engines, thanks to the anonymity that users associate with them, people manifest their true interests. As Bulut indicates

Search query data can be considered as a measure of revealed expectations as because, people key in certain words on the search engines for information they want to learn or for things they have some concerns (Bulut, 2015: 5)

Figure 1 shows the Google search of the terms “Hillary Clinton” and “Donald Trump” in the United States, between August 6th and one day before the election. The graph tells a completely different narrative to that one that resulted from political polls. In fact, in average, the interest manifested to Trump was of 53%, while the one for Hillary Clinton was 47%, very similar to the final results (the final outcome was Trump 46.1% and Hillary Clinton 48.2%).

Figure 1. Search index for “Hillary Clinton” and “Donald Trump” in the United States Source: Google Trends

Source: Google Trends

It is worth mentioning that, in addition to Google, there are other search engines such as Bing, Yahoo, Ask.com, AOL.com, Baidu and DuckDuckGo, among others. In this text I use Google merely because of its popularity among web users.

The next example shows that Google data may predict the demand for vacation destinations. Figure 2 plots both the query index for “Hong Kong” and also the real number of visitors to that destination. The figure contains nine graphs because the visitors are identified by their country of origin. It is remarkable how the forecasted value fits the actual results.

Figure 2. Visitors to Hong Kong Source: Choi and Varian (2011).

Source: Choi and Varian (2011).

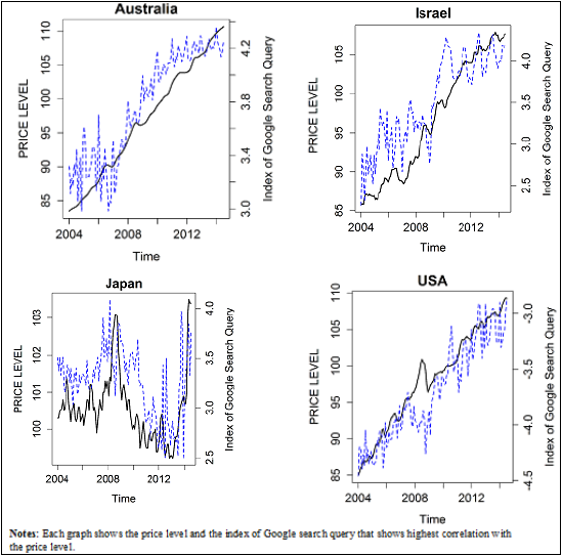

Finally, the third example shows how internet search data can be utilized as a timely description of the state of the economy even before the official data is released (Bulut, 2015). This is an example of how the data from Google can accurately capture the price movements in the economy. Table 1 contains the list of search entries that were used to track the price movements in 10 countries.

Table 1. Google Search Queries Source: Bulut (2015).

Source: Bulut (2015).

Figure 3 plots the price level for Australia, Israel, Japan, U.S.A. and their respective index of Google search query (the query that has the highest correlation with the price level). We observe an important correlation between both variables: the evolution in Google search queries is associated with variations in the price level, which in turn is associated with changes in consumers’ preferences.

Figure 3. Price Level and Google Search Query Index Source: Bulut (2015).

Source: Bulut (2015).

These examples show the wide spectrum of possibilities offered by the web search engines. Thus, in a socialist economy, the central planning bureau would be able both to know the gradation of the values of consumers’s goods and to anticipate the future evolution of consumers’s preferences.

Conclusion

In this paper I proposed a reassessment of the socialist calculation debate. I focused on the question of how to integrate information of consumers’s preferences and argued that the objection raised by Mises and Hayek against the socialist model developed by Oskar Lange can be solved with the current level of technological development, particularly with the use of web search engines. This work may be extended in order to show in formal terms the correspondence between web search queries and consumers’s preferences.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Source: This paper was originally published as Limas, Erick, Cybersocialism: A Reassessment of the Socialist Calculation Debate (February 4, 2018). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3117890 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3117890.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………

[*] Eric Limas (limas.erick@gmail.com) is a Mexican analyst currently living in Berlin. He received his doctorate in economics from the Free University of Berlin. He teaches at School of Business & Economics and Institute for Latin American Studies, Freie Universität of Berlin. He blogs at https://perifractal.wordpress.com/, where he writes about current events and also about how economics, politics, mathematics, philosophy of time and theology can interact with each other.

[*] Eric Limas (limas.erick@gmail.com) is a Mexican analyst currently living in Berlin. He received his doctorate in economics from the Free University of Berlin. He teaches at School of Business & Economics and Institute for Latin American Studies, Freie Universität of Berlin. He blogs at https://perifractal.wordpress.com/, where he writes about current events and also about how economics, politics, mathematics, philosophy of time and theology can interact with each other.

……………………………………………………………………………………….

References

Auerbach, P. and Sotiropoulos, D. (2014). “Revisiting the Socialist Calculation Debate: The Role of Markets and Finance in Hayek’s Response to Lange’s Challenge”. In Toporowski, J. et al., Economic Crisis and Political Economy. Volume 2 of Essays in Honour of Tadeusz Kowalik, Palgrave Macmillan.

Barone, E. (1935[1908]). “The Ministry of Production in the Collectivist State,” in: Hayek, F. A. (ed.) Collectivist Economic Planning: Critical Studies on the Possibilities of Socialism, Routledge and Kegan Paul Limited, London.

Bulut, L. (2015). Google trends and forecasting performance of exchange rate models, Working paper, Department of Economics, Ipek University, 2015.

Cottrell, A. and Cockshott, W. P. (1993). “Calculation, complexity and planning: the socialist calculation debate once again”. Review of Political Economy, vol. 5, pp. 73–112.

Cottrell, A. and Cockshott, W. P. (1993a). Towards a New Socialism. Nottingham: Spokesman.

Desai, M. (2014). “The Walrasian Socialism of Oskar Lange”. In Toporowski, J. et al., The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg, Oskar Lange and Michał Kalecki. Volume 1 of Essays in Honour of Tadeusz Kowalik, Palgrave Macmillan.

Hyunyoung Choi and Hal Varian. (2011). Predicting the present with Google Trends. Technical report, Google, URL http://google.com/googleblogs/pdfs/google_predicting_ the_present.pdf.

Lange, O. (1938). “On the economic theory of socialism.” In Lippincott, B., editor, On the economic theory of socialism. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lange, O. (1970). Introduction to Economic Cybernetics, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Lange, O. (1967). “The computer and the market.” In Feinstein, C., editor, Socialism, capitalism and economic growth: essays presented to Maurice Dobb. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mises, L. (1949). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Samuelson, P. (1938). “A Note on the Pure Theory of Consumers’s Behaviour”. Economica. 5 (17): 61–71.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Notes