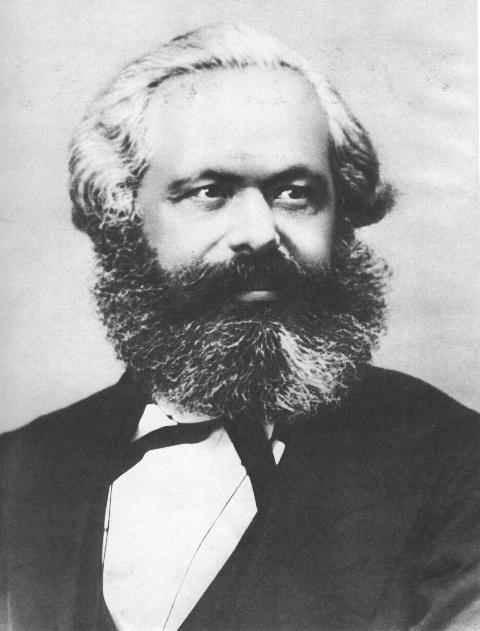

Abstract. Not withstanding their much noted aversion to detailing the nature of a post-capitalist society, Marx and Engels indeed have a broad vision of such a better society that both runs through and informs their entire lives’ work. It is rooted in their concepts of the inherently social nature of humans and potential authentic human development in accord with human nature, and the negation by humans as the active agents of history of the barriers posed to that development. This paper discusses their dialectic approach to defining a better society, their concept of human nature that it rests on, and finally specifies a number general aspects they give for a better future socialist society.

Keywords: Post-capitalist society . Socialist society . Marx and Engels . Better society

Introduction

Any conceived alternative to the currently existing social order can be characterized by different particular institutions and practices. This is the typical approach throughout history of religious or secular utopias, both those that were merely literary exercises and those that were intended for, or even actually used for, application in the real world. Among many others, the works of Moore (1989 [1516]), Campanella (1988[1623]), Fourier (1971), Owen (1991[1813]), Saint-Simon (Markham (1952), Cabet (2003[1840]), Bellamy (1995[1888]), Perkins Gilman (1992 [1915]), Skinner (1976[1948]) and Huxley (1962) are particularly well known examples of such conceptions of a good society. There was seldom any discussion of how humanity could transit from the existing society to the utopia. The implicit concept was that people would read their ideas, recognize them as superior and simply change the social institutions and practices accordingly. Those visions intended for application usually advocated small groups putting the ideas into practice, thus concretely demonstrating the superiority of the ideas and thereby winning over the rest of humanity.

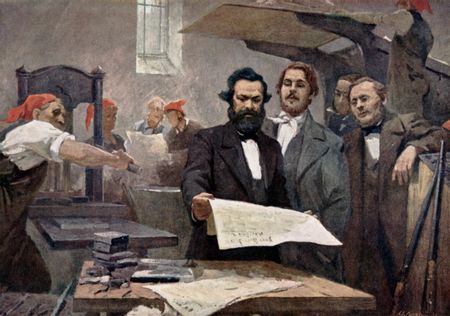

Marx and Engels approached the issues involved in a fundamentally different way. They began with exactly what the others largely left aside, what caused a social order to change to a different social order, and how it changed. They looked to human history for the answers. They then applied the lessons that they drew from history (“historical materialism”) to the dominant contradictions in the present social order to project the general outlines of a better society that would succeed capitalism.

It is correctly commonly accepted that Marx and Engels seldom gave positive descriptions of what would replace capitalism. They extensively described dehumanizing aspects of capitalism, which suggested that these would be negated in a better society. But because they understood history as a contingent and therefore open process of negation of the present, because they understood that there were many more than one way to negate an existing limitation on human development, they indeed gave few predicted descriptions of a post-capitalist society. Despite this general orientation, however, they indeed did give a number of such descriptions (general in character and avoiding details) scattered throughout their lives’ works. The central goal of this short paper is to carefully document a number of these positive predictions, which together do indicate a number of characteristics of the better society that they believed would arise out of the negation of capitalism.

Prior to presenting these positive indications, however, it is necessary to address two preliminaries without which it is not possible to understand Marx and Engels’ understanding of their ideas on a better society (or their lives’ work in general): their dialectical method, and their concept of human nature. These are both very large topics in themselves, and while it will therefore be necessary to address them at some length, there will be no attempt here to address these topics in general and they will be considered only as they relate to their ideas on a better society.

A Better Society and the Dialectics of Marx and Engels

For Marx and Engels all reality, social and natural, is processes. That means that at the same time that the object of consideration is something, that object is also in the process of changing, in the process of becoming something else. To understand a process at a particular moment in time requires two understandings: i) where at that moment the process is at in its development, what phase or stage it is in, and ii) how it is changing, what it is changing toward. The latter, which pertains to the future, can of course only be understood on the basis of information from the present and past.

Marx and Engels consider the nature of the development of these processes to be a continual resolution of contradictions in these processes and the creation of new contradictions from those resolutions. Hence by studying the contradictions in the present phase of a process one can achieve some understanding of where the process will go.

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the now existing premise. (Marx and Engels 1976[1845]: 49).

But it is a mechanistic error to think that one can give a detailed description of how a process will develop from an understanding of the present contradictions. This error rests on the false belief that a given contradiction has only one possible resolution. To the contrary, generally many different resolutions are possible. Which of these actually occurs will depend on the impact of additional factors. This makes processes historically contingent, or open processes.

The concern here, for our issue of the good society, is with the process of human history, the process of the simultaneous development of human society and humans. It was exactly from their studies of the past and especially the capitalist present of society that Marx and Engels were able to sketch some general characteristics of a future better society, as the result of overcoming the present contradictions.

An immediate result of this dialectical approach to progressing to a better future is that the concept of “a good society” is inherently dynamic. In the vision of the utopian authors indicated above, as well as most social reformers, the issue is to replace the institutions, norms and relations that are not satisfactory in the current society. They operate in a comparative static frame, a one-time change from one static state to another. In this frame the concept of “a good society” is simply the better new state. In the Marxist frame, to the contrary, it is more appropriate to talk of “a relative good society” or simply “a better society.” This emphasizes that the new social order will arise out the resolution of problematic contradictions in the present social order, and as such will be good relative to the present. But it will also contain its own contradictions that will rise to become fundamental exactly because of the resolution of the old contradictions. In this frame one can understand this new society as bad in relation to the society that will arise out of the resolution of its primary contradictions. Referring to the development of “a better society” instead of to “a good society” helps to capture the Marxist concept of a historical on-going process of social transformation. In particular, it emphasizes that the process (of human individual, species and social evolution) does not end with the achievement of any particular described “good society.”

An investigation of any of the schemas for a new social order referred to above, however, or even most less-sweeping visions of change advocated by active social reformers today, makes clear that they share many characteristics with the vision of a post-capitalist society of Marx and Engels. This is not surprising since all are driven by a concern with things that seem anti-human in many frames of understanding. These include gross inequality and material impoverishment for many, and alienation, intellectual impoverishment and a lack of power over their own lives and over society (including under the undemocratic systems of capitalist democracy) by the majority. Hence while it is important whether a post-capitalist “good society” is understood as a static goal versus a phase in a process of continual transformation, Marxists must not suffer from any arrogant illusion that this failure to understand the dialectical nature of reality precludes others from championing and fighting for today’s essentials for human progress.

In the political struggle to move beyond capitalism, the dialectical requirement to understand both where a process is at and where it is headed in order to understand a process presents itself in two well-known political problems. If promoters of human progress fail to understand the general nature of where the process of social and human progress is going and how it is developing, they are likely to fall into reformism. That is, because they do not understand that eliminating the fundamental problems of the present social order requires one to resolve its contradictions which requires moving to a new phase in social and human development, they try to find solutions to today’s problems inside the frame of the present capitalist social order. On the other hand, if promoters of human progress fail to understand where at a given moment the process of on-going social and human progress is at, they are likely to fall into ultra-leftism. That is, because they do not understand the objective conditions necessary to allow given transformations and above all the necessary consciousness of the human actors who are the agents of social and human change, they advocate for today their vision of a more developed distant future social order, one that in fact can be achieved only through a process of interacting institutional and human change that extends over time.

The future vision is then not understood by the majority of society as either necessary or even desirable for their self-development, on the basis of their current understanding of their problems with the present social order. Hence even if this vision indeed involves a resolution of many of the principal contradictions that presently constrain further human development, it fails to bring the majority of society into action in its own collective self-interest, which is the only way to effect comprehensive social changes. Both reformism and ultra-leftism serve to protect the existing social order by blocking the development by the masses of an understanding of their own self-interest in transcending capitalism.

A Better Society and Marx and Engels’ Conception of Human Nature

The next section will argue that the goal of a better society for Marx and Engels is that humanity be allowed, and socially supported in, authentic self development. They consider that such development consists of humanity continually more fully developing its authentic nature, both as individuals and as a species. As a necessary preliminary to that, this section will discuss two particular aspects of authentic human nature which they maintain that capitalism presents fundamental barriers to developing.

The first aspect is the social nature of humans. This is an inherent aspect of human nature, and so obtains under any social organization. Capitalism’s false ideology of Robinson Crusoe individualism both obfuscates the understanding of, and distorts the development of, the authentic social nature of humans. As Marx and Engels made clear from their earliest writings in the 1840s, this in turn prevents the understanding of the real individual-society relationship and the development of humanity’s authentic socially conditioned individuality. They hold that developing genuine socially conditioned individuality is central to authentic human development.

It is almost impossible to read Marx and Engels and not understand that they see humans as inherently social beings. The following quote is given at some length because it not only clearly indicates the importance they give to this social nature of humans, but it also indicates the problems caused by the failure to recognize this nature.

Since human nature is the true community of men, by manifesting their nature men create, produce, the human community, the social entity, which is no abstract universal power opposed to the single individual, but is the essential nature of each individual, his own activity, his own life, his own spirit, his own wealth. … as long as man does not recognise himself as man, and therefore has not organised the world in a human way, this community appears in the form of estrangement, because its subject, man, is a being estranged from himself. Men, not as an abstraction, but as real, living, particular individuals, are this entity. Hence, as they are, so is this entity itself. To say that man is estranged from himself, therefore, is the same thing as saying that the society of this estranged man is a caricature of his real community, of his true species-life, that his activity therefore appears to him as a torment, his own creation as an alien power, his wealth as poverty, the essential bond linking him with other men as an unessential bond, and separation from his fellow men, on the other hand, as his true mode of existence, his life as a sacrifice of his life, the realisation of his nature as making his life unreal, his production as the production of his nullity, his power over an object as the power of the object over him, and he himself, the lord of his creation, as the servant of this creation. (Marx 1975 [1844]: 217)

A stereotype of Marxism propagated for over a century by its opponents claims that Marxism sacrifices a concern with the individual to its singular focus on the community. To the contrary, beginning already in the 1840s, their central concern is that capitalism is a barrier to individual as well as species development (where the latter serves individual development). What they stress, however, is that the individual can only be understood as a part of the community, and further, that the community is more than the sum of the individuals, it includes all the interactions between them.

Above all we must avoid postulating “society” again as an abstraction vis-à-vis the individual. The individual is the social being. His manifestations of life — even if they may not appear in the direct form of communal manifestations of life carried out in association with others — are therefore an expression and confirmation of social life. Man’s individual and species-life are not different, however much — and this is inevitable — the mode of existence of the individual is a more particular or more general mode of the life of the species, or the life of the species is a more particular or more general individual life. (Marx 1975 [1844]: 299)

Thirteen years later the “mature Marx” returned to the same theme in notes that were to be a basis for Capital. Immediately after dismissing the idea of the invisible hand as logically unfounded by noting that uncoordinated pursuit of private interest could as logically “hinder the assertion of the interests of everyone” as serve them, Marx goes on to remake this point:

The point is rather that private interest is itself already a socially determined interest and can be attained only within the conditions laid down by society and with the means provided by society and is therefore tied to the reproduction of these conditions and means. It is the interest of private persons; but its content, as well as the form and means of its realization, are given by social conditions that are independent of them all. (Marx 1986[1857]: 94).

Marx and Engels often present this essential social nature of the individual by way of the attack that they maintained throughout their lives on the Robinson Crusoe foundations of economic thought that runs from Smith and Ricardo to mainstream economics today.

Individuals producing in a society — hence the socially determined production of individuals is of course the point of departure. The individual solitary and isolated hunter or fisherman, who serves Adam Smith and Ricardo as a starting point, is one of the unimaginative fantasies of eighteenth-century romances a la Robinson Crusoe. (Marx 1986[1857]: 17)

The second aspect of authentic human nature that will be discussed here, and the one that Marx and Engels repeatedly held was the differentia specifica of humans from other animals, is the potential human consciousness of all aspects of the world that they are part of. The just discussed need to be conscious of humanity’s inherent social nature to develop one’s potential genuine individuality is one example of this. But this need to understand goes far beyond that one issue. Expanded human consciousness of the physical and social processes that we are part of is necessary for the continual change from being the product (“object”) to the producers (“subject”) of those processes. For Marx and Engels that in turn is the goal of human development and the realization of human nature. Engels expressed the centrality of consciousness to authentic human development and the nature of existence in a better society as follows:

With the seizing of the means of production by society, production of commodities is done away with, and, simultaneously, the mastery of the product over the producer. …. The struggle for individual existence disappears. …. The whole sphere of the conditions of life which environ man, and which have hitherto ruled man, now comes under the dominion and control of man, who for the first time becomes the real, conscious lord of nature, because he has now become master of his own social organization. … Only from that time will man himself, with full consciousness, make his own history —only from that time will the social causes set in movement by him have, in the main and in a constantly growing measure, the results intended by him. It is humanity’s leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom. (Engels 1987[1878]: 270)

Characteristics of a Better Society: General and (Some) Specifics

Any discussion that aspires to discuss a better society logically must begin by establishing the goal it will use to measure what is better. If one’s goal is to have a minority of society both live better materially and exercise economic and political domination over the majority of society, for example, a capitalist political economy would be better than the socialist and communist societies (partially) envisioned by Marx and Engels.

Marx and Engels’ vision of a better society has a single central goal, which can be, and often has been, expressed in many different ways. Among the common formulations are “authentic human development,” “the development of one’s human potential,” “the opportunity to develop potential abilities or capabilities,” “becoming more fully human,” “developing one’s species-nature,” and a phrase Marx and Engels used often, “the development of [human] freedom.” The following reflects this latter usage, and we see here also as indicated above their stress on the development of all (social) individuals, and how they saw that as requiring collective control of (which in turn requires consciousness of) their collective productivity.

Free individuals, based on the universal development of the individuals and on their subordination of their communal, social productivity which is their social possession [Vermögen]. (Marx 1989[1875]: 95)

With this as the goal, a general way to characterize a better society would obviously be as one that allows and facilitates this goal.

… what has to be done is to arrange the empirical world in such a way that man experiences and becomes accustomed to what is truly human in it and that he becomes aware of himself as a man. If correctly understood interest is the principle of all of morality, man’s private interest must be made to coincide with the interest of humanity. (Engels 1975[1845]: 130–1)

It is well known that Marxism opposes proposing the sort of detailed prescriptions for a better society that would be consistent with their general goal, and that they attacked St Simon and Fourier for doing so. Notwithstanding this, many indications of their general vision of parts of the nature of future socialist and communist societies are distributed throughout their collected writings. These general considerations arise from the combination of humanity’s goal and the dialectical method of logic discussed above. Given the human drive for individual and species development and the barriers to that presented by capitalism, they can project general characteristics of these better future societies as the negations of those limitations.

A thorough study of their writings would yield scores of such indications of parts of their general vision of a socialist and communist society. Presented here are only eleven. The single densest presentation of their ideas on these future better societies is in The Critique of the Gotha Programme. That will be drawn on most heavily here, but it must be stressed that these indications are dispersed throughout the whole body of their work.

As discussed above, the process of transition from capitalism to socialism and then to communism and beyond is understood by Marx and Engels as an uninterrupted process of human development. Earlier changes in that process will be negations of barriers in capitalism as it exists today, while later changes will also include negations of some of the institutions and human relations that arise as negations of capitalism. It is of course easier to see the earlier changes, and the discussion here concerns the socialist phase in the process of the transition to communism and beyond.

Most of the characteristics of a better society that will be listed come directly from statements by Marx and Engels, and will be so referenced. A few are logical conclusions from other points listed, which will also be so indicated. Note the nature of these characteristics, as asserted above, as negations of capitalism, as the elimination of capitalism’s barriers to authentic human development.

- A collective society. (the discussion above on humanity’s inherent social nature; Marx 1989[1875]: 85)

- Democratic decision making. (Marx 1975[1843]: 30–1; Marx and Engels 1984 [1848]: 504)

- Common ownership of the means of production. (Marx 1996[1867]: 89, 1989 [1875]: 85)

- Only the means of consumption can be individually owned. (Marx 1989 [1875]: 86)

- Three ways to say the same thing: i) No production of value. (Marx 1989 [1875]: 85); ii) Individual labor no longer exists in an indirect fashion. (Marx 1989[1875]: 85); iii) Individual labor will now be consciously applied as the combined labor power of the community. (Marx 1996[1867]: 89, 1989 [1875]: 85)

- No money. This follows directly from 5, but Marx also makes this clear in many places in his writings, such as for example (1986[1857]: 107–9).

- The producers do not exchange their products. (Marx 1989[1875]: 85) Note particularly that this does not imply that there will not be a division of labor, as there will be. People will consume things produced by others, but goods will not be “exchanged,” as will be further explained. They of course could not be exchanged in the way of capitalism, since the goods do not have a

- No capitalist markets. This follows directly from 5, 6 and 7.

- Social Planning will replace capitalist markets as the mechanism that organizes the economy, both production and distribution. Note particularly that point implies that something other than capitalist markets must organize the economy. Marx calls for planning scores of times in his writings throughout his life as the necessary way to organize a post-capitalist

- A point which is often not recognized—the socialist system that Marx described would pay everyone the same wage, one “labor-credit” (a certificate to receive goods that took one hour of social labor to create) for every hour of social work by any person. (Marx 1989[1875]: 86, 1996[1867]: 89, 1996 [1867]: 104, fn 1) Note in relation to this that it is sometimes incorrectly asserted that Marx opposed labor credit systems because of his repeated attacks on authors who advocated using them in capitalism to mitigate its harmful effects, where he argued that labor certificates are incompatible with commodity production. But there is no such incompatibility for production by “directly associated labor” as this note indicates Owen proposed, or as Marx here directly calls for in Again keep in mind this is a description of a socialist phase, not a phase (or phases) of a transition from capitalism to socialism, when wages might still be unequal as in capitalism. As a process, the wage spread would therefore narrow as one approached the phase of socialism in the transition beyond capitalism.

- A little commented on aspect of Marx’s concept of socialism that he stresses at length in the Critique is that the same principle prevails in socialism (but not in communism) that regulates capitalist exchange, the exchange of equivalents. To be sure, he notes that this principal is actually realized under socialism, while it is deformed under capitalism because of the existence exploitation. Nevertheless, a surprising aspect of Marx and Engel’s vision of socialism is that it will continue to rest on this bourgeois right (Marx 1989[1875]: 86), the capitalist concept of what is right or just. One central aspect of communism as a continuation of the process of human development beyond socialism will be exactly transcending this concept of right. (Marx, 1989[1875]: 87)

The topic of this paper is the nearer phase of the transition beyond capitalism, socialism, because more aspects of its nature can be seen in (the negation of) existing capitalism. However, to underline the point made above concerning the nature of “the better society” as an unending process of transformation, here I will just mention two characteristics of socialism that Marx and Engels argued would have to be negated to build communism: the nature of work and, as already noted, the concept of right or justice. Because of the limitation on the length of this paper these issues cannot be actually discussed here, but they will be presented in a subsequent longer version of this essay.

Conclusion

Not withstanding their much noted aversion to detailing the nature of a post-capitalist society, Marx and Engels indeed have a general vision of such a better society that both runs through and informs their entire lives’ work. It is rooted in their concepts of the inherently social nature of humans and potential authentic human development in accord with human nature, and the negation by humans as the active agents of history of the barriers posed to that development. This process is understood as a dialectical interaction of the transformation of the social institutions that influences the development of humans and the transformation of humans that influences the development of social institutions. Broadly then, their vision of a better society is one where the institutions support and promoted the authentic development of humans, and humans support and promote the continual development of new institutions that will constantly move forward the unending process of human development. Among the general characteristics of a near-term post-capitalist (socialist) society that they specifically mentions are a collective society, democratic decision making, common ownership of the means of production, the end of money and markets and their replacement with democratic planning, individual labor carried out consciously as part of the total social labor, and an equal claim on the social product in accord with the time one contributes to social production. More abstractly, they refer to the process of the continual transcendence of what exists by the further transcendence of the socialist phase of human development with the development of new communistic conceptions and practices of work and of justice.

References

Bellamy, E. (1995[1888]). Looking backward: 2000–1887. Boston: Bedford Books.

Cabet, E. (2003[1840]). Travels in Icaria. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Campanella, T. (1988[1623]). City of the sun. In Henry Morely, Ideal Commonwealths.

Engels, F. (1975[1845]). Karl Marx Frederick Engels collected works (hereafter MECW), Vol. 4. Moscow: Progress. The Holy Family.

Engels, F. (1987[1878]). MECW, Vol. 25. Moscow: Progress. Anti-Dühring.

Fourier, C. (1971). Design for Utopia: Selected writings of Charles Fourier. New York: Schocken Books. Huxley, A. (1962). Island. New York: Harper & Row.

Markham, F. M. H. (Ed.). (1952). Selected writings. Henri Comte de Saint-Simon. Oxford: Blackwell.

Marx, K. (1975). Karl Marx Frederick Engels collected works (hereafter MECW), Vol 3. Moscow: Progress Publishers. ([1843] Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law; [1844] Comments on James Mill, Élémens d’Économie Politique; [1844] Economic and Political Manuscripts of 1844.

Marx, K. (1986[1857]). MECW, Vol 28. Moscow: Progress. Grundrisse.

Marx, K. (1996[1867]). MECW, Vol 35. New York: International Publishers. Capital, Vol I. Marx, K. (1989[1875]). MECW, Vol 24. Moscow: Progress. Critique of the Gotha Programme.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1976[1845]). MECW, Vol 5. New York: International Publishers. The German Ideology.

Marx, Karl, & Engels, F. (1984[1848]). MECW, Vol 6. Moscow: Progress. Manifesto of the Communist Party.

More, T. (1989[1516]). Utopia. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

Owen, R. (1991[1813]). A new view of society and other writings. London: Penguin. Perkins Gilman, C. (1992[1915]). Herland. New York: Signet.

Skinner, B. F. (1976[1948]). Walden Two. New York: Macmillan.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Source: This paper was originally prepared for and presented at the Association for Social Economics, session Alternative Perspectives of a “Good Society” at the ASSA meetings in Atlanta on January 4, 2010. It was published online: 23 June 2010 # Association for Social Economics 2010. For Soc Econ (2010) 39:269–278, DOI 10.1007/s12143-010-9075.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

[*] Al Campbell (Al@economics.utah.edu) is an Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of Utah, USA.Co-Editor of the International Journal of Cuban Studies and coordinator of the Moving Beyond Capitalism working group in the International Initiative for Promoting Political Economy. The three pillars of his research interests are the functioning of contemporary capitalism, all human-centered theoretical alternatives to it, and all historical experiments in trying to build an alternative. Much of the work on the latter has been on Cuba, with his latest book an edited collection by Cuban authors (Cuban Economists on the Cuban Economy), and he is presently co-editing a collection of contributions by Cuban authors on Cuban cooperatives.