ABSTRACT: The labor theory of value provides both a moral and a conceptual foundation for an equitable and efficient socialism. Given modern information technology, a system of planning can work. Markets in consumer goods are required, but not markets for the means of production. We advocate a system of payment in labor-tokens, and argue for its superiority over the wages system in terms of both equity and economic efficiency.

1. Introduction

THE MOST INFLUENTIAL PHILOSOPHER of the last two centuries was Karl Marx. Among philosophers he was unusual both in being a communist and in being an expert in economics. The fact that Marx wrote extensively on economics has led some to call him an economist, but this is misleading. The two principal works on the subject that he published during his lifetime (Marx, 1971a [1859] and Marx, 1970 [1867]) were both titled «critiques of political economy.» They were demolition jobs on political economy from the standpoint of communist philosophy, which sought to reveal how the categories used by the political economists — money, price, profit, capital — are not fundamental. Instead, Marx argued, they are expressions of historically specific forms of social relations, which, with changes in social relations, could disappear.

Following the counter-revolutions in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, bourgeois thinkers proclaimed that Marx had been proved wrong in practice — that money, price, profit and the rest have indeed been shown to be fundamentals of any modern society. (…)

In the following pages we reconstruct a concept of socialism that is at once consistent with the conceptual framework of Marx’s writings on economics and influenced by the lessons of hitherto-existing socialism.1 We differ from most people writing on socialism in the years since the collapse of Communism in that we continue to advocate a planned economy. In doing so we are in the company of David Laibman (1992). (…)

2. The Theory of Value

The labor theory of value is the conceptual foundation of all Marx’s writing on economics. Our claim is that it also provides both a moral philosophy and a set of economic policies for socialism. Ironically, both the philosophy and the policies have been effectively ignored by orthodox Marxism-Leninism. The theory of value has been relegated to the analysis of capitalism, and dismissed as of no relevance to socialism.

2.1. Philosophical approach. One of Marx’s philosophical axioms was that appearances can be deceptive: «That in their appearance things often represent themselves in inverted form is pretty well known in every science except political economy» (Marx, 1970, 537). In astronomy the appearance is of a fixed earth and an orbiting sun, the opposite of the reality. The task of science is to uncover the underlying causal mechanisms that give rise to these appearances. In economics, the appearance is that things are valuable because people are willing to pay money for them. The foundation of scientific political economy with Adam Smith starts out from the recognition that this is an illusion, that there is an underlying cause of prices that is independent of the subjective wishes of purchasers.

2.2. Value. «The value of a thing is the number of hours of society’s labor needed to make it» (Marx, 1970, 38-39). It is important to recognize that value exists prior to, and independently of, sale, and thus its appearance as exchange value. At any given time, the labor needed to produce any given object is an objective fact. If a car requires 1000 hours for its production, that is what it has cost society. In a market economy, this social cost will determine its exchange value. But even if the product is never brought to market (as with a Ford engine used within the Ford Motor Company) a portion of society’s labor went into its production and thus it has value. Generalizing, the concept of value, or social labor time, also applies to non-market economies.2

2.3. Exchange value. Exchange value is the specific form assumed by value in market economies. In a market economy, the relative prices or exchange values of commodities are determined by their value, their labor content.3 For value to appear as exchange value a large number of independent producers and/or consumers must exist. The labor of these independent producers is unplanned. Only when their products are exchanged does the necessary social labor content of the products get measured. The measurement performed by the market assesses the necessity of the labor in two senses — whether the commodity was produced efficiently, and whether it was produced in the “right” quantity. If a firm uses out-of-date production techniques, it will have wasted social labor; this is reflected in its commodities selling for less than their actual labor content. If too much of a commodity comes onto the market, again social labor has been wasted and the price will be below its actual labor content. In this way the market validates the social necessity of privately performed labor.

The socialization, via the market, of labor performed in independent capitalist enterprises is, however, highly imperfect. Market prices only tell you about present conditions. Suppose that in 1994 a computer costs $1000. Thinking this good value, 30 million customers around the world decide to buy one. Manufacturers, in response to demand, place orders for memory and microprocessor chips. It is soon discovered that the chip factories do not have the capacity to meet the demand. The prices quoted for chips were not sufficient to cover the costs of opening new production lines. Delivery times on chips rise to three months, four months, six months. Seeing this, Fujitsu, Oki and Hitachi put up their chip prices and build new factories. In the meantime, the price of computers is put up to $1300. By the time new plants are in production, demand for computers has fallen off, prices collapse, and newly opened factories have to close.

This sort of instability, which occurs on a cyclical basis in most industries, is an inevitable consequence of the limited bandwidth of the channel that passes information in a market economy: price.

2.4. Value of labor power. If labor is taken as the substance of value, then the value of labor itself is always unity. An hour of labor is worth an hour of labor. Since hourly wages vary, and since the goods that can be bought with an hour’s wages invariably cost less than an hour to make, it is clear that either workers are systematically cheated by being paid less than the value of their labor (this was the conclusion of Rodbertus 4); or wages are not actually the price of labor, but the cost of hire of the ability to work (the view adopted by Marx).

Marx’s view has perhaps more logical elegance. Whichever view one adopts, the conclusion is much the same: Capitalism leads to workers being exploited.

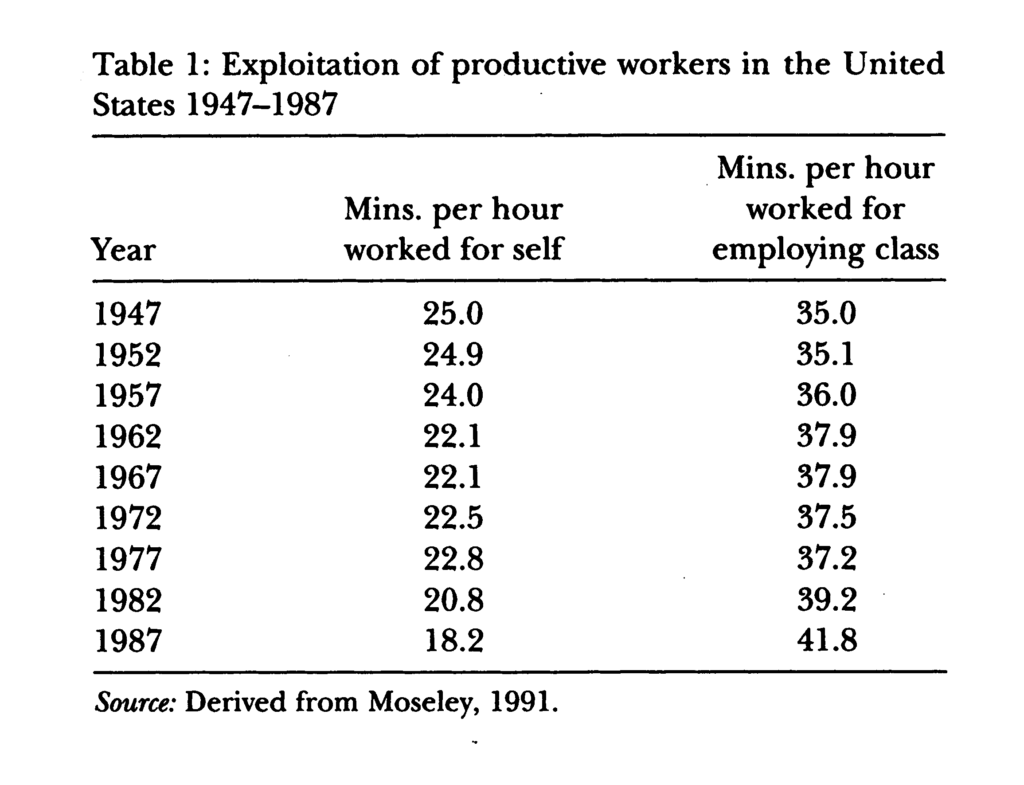

2.5. Exploitation. Exploitation is being forced to do unpaid work for others. In some cases unpaid labor appears as such – the work of the slave for the master or a wife for her husband. It may be disguised in terms of love or duty, but that it is unpaid is beyond question. In the case of wage labor, it is only possible to detect exploitation if you know how many minutes’ work are required to produce the goods that can be bought with an hour’s wages. Since this is difficult to work out, workers are unlikely to realize just how much they are exploited. But the breakdown of the working day can be calculated from macroeconomic statistics, as in Table 1. The table records, at five-year intervals, how the value added through labor has been distributed between the workers and their bosses. We can see that as time went on the number of minutes per hour that workers put in for their bosses — the surplus labor time — tended to rise. By the end of the period, productive workers were working only about 18 minutes per hour to pay their own wages, the remaining time going to the benefit of the employing class.

2.6. Value and efficiency. Not only is capitalist exploitation unjust; it also leads to economic inefficiency in the form of the wasting of labor time, society’s key resource. Capitalists aim to minimize their costs of production. They can do this in two main ways: Make their workers work longer hours for lower wages, and/or adopt a more efficient technology. To the capitalist it is a matter of indifference how she cuts her costs. If sweated labor is cheaper than adopting new technology, then sweated labor it will have to be. The capitalist buys her labor by the hour and is reluctant to waste it. She employs time and motion study to check that she is making good use of what she has bought. But still, she buys labor cheap; if she did not, there would be no profit in it.

The lower wages are, the greater the profit, but when wages are low employers can afford to squander labor. The capitalist is one step above the slaveholder in rationality, but that step can be a small one. For instance, the “navigators” who built Britain’s railway system in the Victorian era worked with the same tools as Hadrian’s slaves building roads and aqueducts: muscle power, pick and shovel. The one great technical advance in two millennia was the wheelbarrow, a Chinese invention. The navvies had it, the slaves did not. The railway was the product of the machine age; it was not beyond the wit of Stevenson or Brunei to design steam-powered mechanical excavators. They did not bother because wage slaves could be had cheap.

This is a point which Marx analyzed at some length in Capital:

Suppose, then, a machine cost as much as the wages for a year of the 150 men that it displaces, say £3,000; this £3,000 is by no means the expression in money of the labour added to the object produced by these 150 men before the introduction of the machine, but only of the portion of their year’s labour which was expended for themselves and represented by their wages. On the other hand, the £3,000, the money value of the machine, expresses all the labour expended on its production, no matter in what proportion this labour constitutes wages for the workman, and surplus value for the capitalist. Therefore, though a machine costs as much as the labour power displaced by it costs, yet the labour materialised in it is even then much less than the living labour it replaces. (Marx, 1970, 392.)

Marx then goes on to define what a rational criterion for the employment of machinery would be: «The use of machinery for the exclusive purpose of cheapening the product, is limited in this way, that less labour must be expended in producing the machinery than is displaced by the employment of the machinery» (Marx, 1970, 392) . This limit would act as an upper bound in any mode of production, but this degree of rationality cannot be achieved in a capitalist economy. To each mode of production there exists its own proper form of economic calculation, its own proper form of economizing. «For the capitalist, however, this use is still more limited. Instead of paying for the labour, he pays only the value of the labour power employed; therefore the limit to his using a machine is fixed by the difference between the value of the machine and the value of the labour power replaced by it» (Marx, 1970, 392).

As so often in Capital, Marx is able to make these critical observations regarding capitalist production because, at least in his mind’s eye, he is looking back at it from the standpoint of communism. One can only criticize a system once one can visualize an alternative. Just as Smith’s critique of the unproductive expenditures of the land-owning class was an anticipation of a fully bourgeois form of economy, Marx’s criticism here is an anticipation of communism. It is an anticipation in which the fetishistic historically partial form of economic calculation brought about by the monetary rationality of the market is replaced by a direct calculation of social rather than private costs. Here is the key implication of the whole critique of commodity fetish- ism: This calculation can only be in terms of labor-time; of value, not price5.

3. Socialism and Value

It follows from the definition given above that value exists in any society with a social division of labor, which must include socialism. The question is how value appears in a socialist economy. Marx believed that in a socialist commonwealth value relations would appear transparently as relations of labor time, rather than via the mediation of exchange value:

Let us now picture to ourselves … a community of free individuals, carrying on their work with the means of production in common, in which the labour-power of all the different individuals is consciously applied as the combined labour-power of the community. All of the characteristics of Robinson [Crusoe]’s labour are here repeated, but with this difference, that they are social instead of individual. Everything produced by him was exclusively the result of his own personal labour, and therefore only an object of use for himself. The total product of our community is a social product. One portion serves as fresh means of production and remains social. But another portion is consumed by the members as means of subsistence. A distribution of this portion among them is consequently necessary. The mode of this distribution will vary with the productive orga- nization of the community, and the degree of historical development attained by the producers. We will assume, but merely for the sake of a parallel with the production of commodities, that the share of each individual producer in the means of subsistence is determined by his labour-time. Labour-time would, in that case, play a double part. Its apportionment in accordance with a definite social plan maintains the proper proportion between the different kinds of work to be done and the various wants of the community. On the other hand, it also serves as a measure of the portion of the common labour borne by each individual, and of his share in the part of the total product destined for individual consumption. The social relations of the individual producers, with regard both to their labour and to its products, are in this case perfectly simple and intelligible, and that with regard not only to production but also to distribution. (Marx, 1970, 78-79.)

This passage contains two ideas that we develop further below: first, the idea of a socialist system of payment in the form of labor tokens, an egalitarian replacement for the capitalist wages system; and second, the idea of a socialist planning system using social labor time as its unit of account and basic principle of costing. It is noteworthy that no actual socialist society of the 20th century has done as Marx envisaged — namely, eliminated money and substituted a labor-time accounting system — yet we shall argue that this is both feasible and desirable on grounds of both equity and efficiency.

We begin by expanding on the idea of payment in labor tokens.

3.1. Payment in labor tokens. It was a common assumption of 19th-century socialism that people should be paid in labor tokens. We encounter the idea in various forms in Owen, Marx, Lassalle, Rodbertus and Proudhon. Debate centered on whether or not this implied a fully planned economy.6 With the enthusiasm of a pioneer, Owen tried to introduce the principle into England via voluntary cooperatives. Later socialists concluded that Owen’s goal would be attainable only with the complete replacement of the capitalist economy. The significance of labor tokens is that they establish the obligation on all to work by abolishing unearned incomes; they make the economic relations among people transparently obvious; and they are egalitarian, ensuring that all labor is counted as equal. It is the last point that ensured that they were never adopted under the bureaucratic state socialisms of the 20th century. What ruler or manager was willing to see his work as equal to that of a mere laborer? In a labor-token system, workers are credited with the number of hours of work they perform. These labor-time balances (which nowadays could take the form of accounting entries stored in the equivalent of an ATM card) are canceled against the acquisition of consumer goods that require a corresponding amount of labor for their production. Labor tokens therefore do not circulate, and they cannot be used to purchase labor-power, i.e., they cannot be turned into capital. It was this feature that led Marx to state that Robert Owen’s «labor-money» was «no more ‘money’ than a theatre ticket is.»

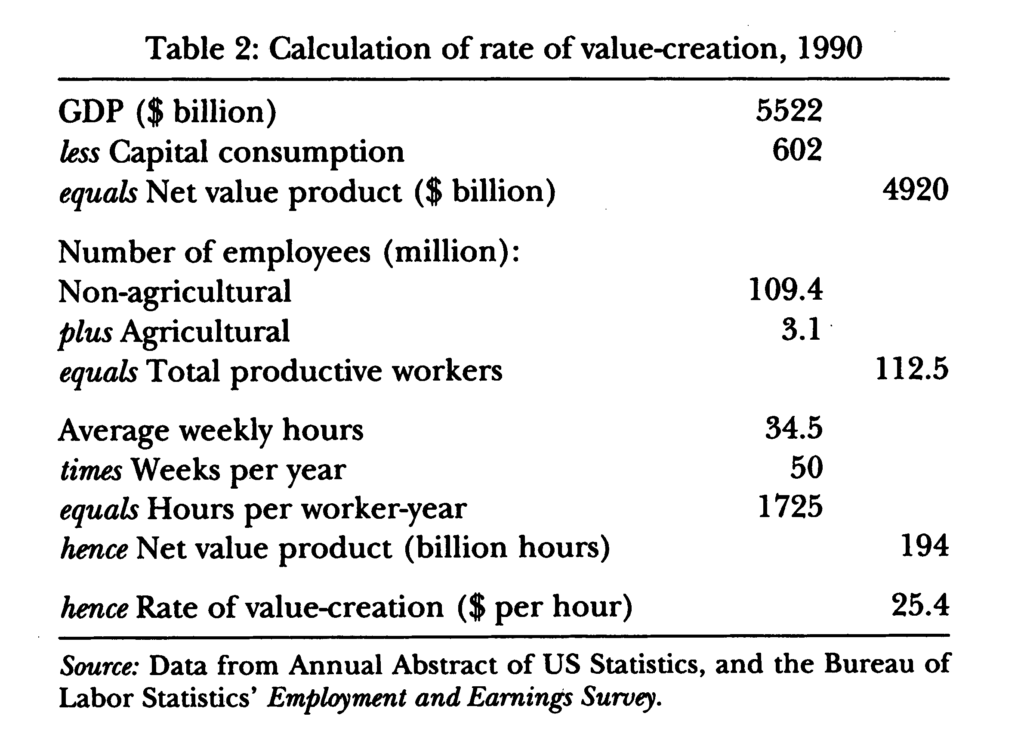

3.2. Who would gain? How much better off would the average person be under the socialist system of payment? How much would one hour’s labor produce? We estimate that in the United States in 1990 an hour’s labor produced goods worth about $25 (see Table 2). This means that payment in terms of labor tokens would be equivalent to an hourly rate of $25 per hour in 1990 money, or about $875 for a 34.5-hour week. This is of course before tax.

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics figures, the median weekly income for women workers in 1990 was $348. Given an egalitarian pay scale of $875 a week, the majority of the female workforce would have seen their incomes more than doubled. Although men are generally paid about a third more than women, the great majority of men also would benefit from the socialist principle of payment according to labor. The median male wage was $485, so the majority of male workers would see wage increases of more than 75 per cent. What this shows is that the great majority of employees are exploited. The gains they would make if they were no longer exploited would more than offset any erosion of differentials under an egalitarian pay scheme. These gains are possible because property income is abolished under a socialist system of payment.

3.3. Skilled labor. The obvious objection to an egalitarian payment system is that it makes no provision for different types of labor. In capitalist economies relatively skilled or educated labor power is generally better paid. Why?

The standard idea is that this salary premium compensates for the expenses of education or training, and for earnings foregone. The extent to which people in capitalist economies pay for their own education varies, but in all cases there is an element of earnings foregone, in that people could earn more (at first) by going straight into employment after completing the basic education than they will receive during the extra years of education. To ensure a sufficient supply of educated labor power, therefore, the more highly educated workers must be paid a premium once they move into employment.

But how realistic is this? Is it really a sacrifice to be a student compared, for instance, to leaving school and working on a building site? Compared to many working-class youngsters, students have an easy time. The work is clean. It is not too demanding. There are good social facilities and a rich cultural life. Is this an experience that demands financial compensation in later life?

Even if the compensation argument is an accurate reflection of reality in capitalist countries this does not mean that professional workers should obtain the same sort of differentials in a socialist commonwealth. The costs of education and training then would be borne fully by the state. Not only would the education itself be free, as it has been in Britain, but in addition students could receive a regular wage during their period of study. Study is a valid and socially necessary form of work. It produces skilled labor as its “output,” and should be rewarded accordingly. There need be no individual expense or earnings-loss on the part of a student that has to be compensated for.

The class system prevents a large part of the population from reaching their full potential. Children grow up in deprived areas without ever realizing the opportunities that education presents. Their aspirations stunted from infancy, the majority, with some realism, assume that only menial work is open to them; and who needs an education for that? This attitude reflects the jobs that children see their parents doing, and these jobs would not immediately change if a revolution in society instituted equal pay. Equality would not raise the educational and cultural levels overnight; but in time the democratic presumption behind it would. Equal pay is a moral statement. It says that one person is worth as much as any other.

Talk of equality of educational opportunity is just cant so long as hard economic reality reminds you that society considers you inferior. Beyond what it buys, pay is a symbol of social status, of esteem and self-esteem. Level pay and you will produce a revolution in self-esteem. Along with the comfort and security it would bring to the mass of people would come a rise in their expectations for themselves and their children.

3.4. Taxes. We said above that in 1990 the average worker would have had an income of $25 per hour, were they paid the full value of their labor. We do not say that everybody would be free to spend all of this each week. There would still be taxes. In a socialist commonwealth the level of personal taxation to support education, health services, public investment, scientific research and so on is likely to be higher than at present. As against this, less tax would have to be needed to fund social security in a fully employed socialist economy. But an allocation of national income through the taxation system is fundamentally different from exploitation because the tax system can be subject to democratic control.

In a democracy where the citizens can influence the level of taxation, taxes represent resources that people have consented to allocate to public purposes. By contrast, the distribution of income brought about by the market economy is not, and can never be, the result of democratic decisions. But nor can it be said that our present tax system is fundamentally democratic. The only democratic tax change is one approved by plebiscite.

How can complicated questions like taxes be reduced to simple yes/no questions that the people can vote on? Here again Marx’s economic writings point a way forward. Marx describes how the working day of wage laborers is divided into two parts, one of which they spend working for themselves (to pay their wages) and another during which they work for their employer.

We have seen that the labourer, during one portion of the labour-process, produces . . . the value of his means of subsistence If the value of those necessaries represents on an average the expenditure of six hours’ labour, the workman must on average work for six hours to produce that value. (Marx, 1970, 216.)

During the second period of the labour-process, that in which his labour is no longer necessary labour, the workman . . . creates surplus-value which, for the capitalist, has all the charms of creation out of nothing. This portion of the working-day I name surplus labour-time, and to the labour expended during that time, I give the name of surplus-labour. (Marx, 1970, 217.)

In a socialist society we can still speak of surplus labor. No longer would labor be devoted to producing luxuries for the wealthy, but any net investment by society must come under the heading of sur-plus. Work to support the non-producers (children, the retired and the invalids) can, on the other hand, only be considered surplus from the most individualistic standpoint. From the point of view of society as a whole this labor is necessary, and, considering a person’s whole life, the hours that she puts in during her working life to support the young, the sick and the old would be balanced by the times that she herself is supported by others. Nevertheless, while working, we as individuals are not free to consume that portion of the national product that goes to pay pensions or run the hospitals and schools.

Taxes must be deducted from our incomes to pay for it.

Issues of taxation could be presented to people in this sort of way: «How many hours are you willing to work per week to support the public health system? It is presently three hours per week; do you want to (1) reduce this by 10 minutes, (2) leave it the same, or (3) increase it by 10 minutes?» Then people would have something that they could understand. Such questions could readily be put in a referendum so that each year the annual budget was approved by the whole people.

3.5. Forms of taxation. What would be the best form of taxes in a socialist commonwealth? The USSR traditionally raised most of its state revenue from a sales or turnover tax on the produce of nationalized industry. This gave the illusion that people were not heavily taxed, since income tax could be kept down to negligible levels and it is taxes on income that are most visible. The effect, however, was to depress the price of labor relative to other commodities, with the deleterious effects described above. There is a better alternative.

Ironically, in view of the strenuous efforts made by Marxists to oppose the “Community Charge” (better known as the poll tax) under Mrs. Thatcher’s Tory government, a poll tax would actually be a good tax in a socialist commonwealth. The obvious objection to such a tax under capitalism is that it is regressive, but if everybody earned the same hourly rate then this objection would fall, provided that those who had retired or were unable to work were exempted.

The advantage of a poll tax in a commonwealth is that it establishes that all have the same obligation to work for the common good before they work for themselves. Once you have done your three hours a day (say) to pay your tax, each additional hour worked will be your own. For every additional hour, you will get goods that had cost society one hour to produce.

4. Prices under Socialism

4.1. Communism cannot abolish scarcity. The capacity of any society to produce is finite. So too, is the demand for any one particular good. Some goods, e.g., water in a rainy country, can be produced to satisfy our needs with a minimal expenditure of labor. But by definition these goods account for only a small part of the value of a nation’s output. The more valuable part is hard won by labor, our ultimate scarce resource.7

Technology may reduce the labor required for some things, or even abolish whole branches of the division of labor. But as fast as it does this it creates new trades and specialisms, and, by opening up new vistas of the possible, engenders new and more sophisticated tastes. By the standards of the 19th-century founders of the socialist movement, the workers of Eastern Europe in 1989 lived a life of plenty: Owen and Lassalle had never heard of CDs and videos.

It is a fact, not of economics but of geology, that 1,200,000,000 Chinese and 700,000,000 Indians are not all going to be able to drive BMWs. Since scarcity cannot be wished away, socialism must have a practical and fair way of dealing with it. Basically, there are two options, the rationing of scarce goods, or a price system of some kind. Rationing makes good sense for services such as health care, where needs can be determined objectively rather than subjectively. In countries with socialized medicine decisions about the medical procedures needed by a patient are made by doctors, not patients. The assumption is that doctors are better placed to arrive at an ob- jective assessment of what is wrong with the patient, and thus the treatment needed, than the patients themselves. Where needs are best judged by the individual, on the other hand, the wisdom of rationing depends on the distribution of income.

Rationing is the best way of ensuring that scarce goods are fairly distributed if incomes are unequal, since it prevents the rich from cornering the market. In case of food in an emergency, formal rationing will ensure that everyone can get enough to survive. Given the sort of egalitarian income distribution discussed earlier, however, a price system is more efficient than rationing.

4.2. The limited role for markets. Advocates of the market compare it to a system of voting which makes the consumer “sovereign.” This it does, but as Rodbertus long ago pointed out, 8 the consumers and the people are two different groups. Consumers are those with money. Only those who already possess something can have their wants satisfied. The unemployed, with only their unwanted labor to offer, have no votes in this system.

If, however, we first posit an egalitarian income distribution, this objection to the market falls. So long as the market is restricted to consumer goods, there is no reason why it should be incompatible with socialism.

The basic principle of a socialist market in consumer goods can be stated quite simply. All consumer goods are marked with their labor values, i.e., the total amount of social labor which is required to produce them. 9 But aside from this, the actual prices (in labor tokens) of consumer goods will be set, so far as possible, at market-clearing levels. Market-clearing prices are prices which balance the supply of goods (previously decided upon when the plan is formulated) and the demand. By definition, these prices avoid manifest shortages and surpluses. The appearance of a shortage (excess demand) will result in a rise in price that will cause consumers to reduce their consumption of the good in question. The available supply will then go to those who are willing to pay the most. The appearance of a surplus will result in a fall in price, encouraging consumers to increase their demands for the item.

Suppose a radio requires 10 hours of labor. It will then be marked with a labor value of 10 hours, but if an excess demand emerges the price will be raised so as to eliminate the excess demand. Suppose this price happens to be 12 labor tokens. The radio then has a price to labor-value ratio of 12/10, or 1.2. Planners (or their computers) record this ratio for each consumer good. The ratio will vary from product to product, sometimes around 1.0, sometimes above (if the product is in strong demand), and sometimes below (if the product is relatively unpopular). The planners then follow this rule: Increase the target output of goods with a ratio in excess of 1.0, and reduce it for those with a ratio less than 1.0.

The point is that these ratios provide a measure of the effectiveness of social labor in meeting consumers’ needs across the different industries. If a product has a ratio of market-clearing price to labor value above 1.0, this indicates that people are willing to spend more labor tokens on the item (i.e., work more hours to acquire it) than the labor time required to produce it. But this in turn indicates that the labor devoted to producing this product is of above-average social effectiveness. Conversely, if the market-clearing price falls below the labor value, that tells us that consumers do not “value” the product at its full value: Labor devoted to this good is of below-average effectiveness. Parity, or a ratio of 1.0, is an equilibrium condition: In this case consumers “value” the product, in terms of their own labor time, at just what it costs society to produce it.

There are therefore two mechanisms whereby the citizens of a socialist commonwealth can determine the allocation of their combined labor time. At one level, they vote periodically on the allocation of their labor between broadly defined uses such as consumer goods, investment in means of production, and the health service. At another level, they “vote” on the allocation of labor within the consumer goods sector via the spending of their labor tokens.

4.3. Environmental pricing. A possible criticism of using labor values in economic calculation is that they cannot take into account environmental costs. This is valid, but the same applies to using money. Endangered species have no money to pay for their own protection. If environmental factors do enter into the accounts of profit and loss it is only indirectly — for example, by having the government levy a carbon tax on fuel to deter atmospheric pollution.

A planned economy could produce the same effect by more direct means. It could set physical targets for carbon consumption at so many million tons a year. These limits can be fed in as constraints to the planning computers, which on the basis of their knowledge of current technology can compute how production must be adjusted to deal with the new conditions. A consequence will be that planned production of carbon-intensive consumer goods is restricted. Coal for domestic heating will rise in price relative to natural gas. This kind of premium would be permanent, not a transitory phenomenon of adjustment, and would, like a carbon tax, provide a source of public revenue.

5. Planning

A few decades ago there was little doubt in the minds of socialists that planning was the wave of the future. This was borne out by the rapid advance of the planned economies, which with sputnik and Gagarin seemed to outpace the muddled inefficiency of the capitalist economies. Today, of course, the picture looks different.

Ever since the 1920s bourgeois economists had been claiming that the problems of economic calculation involved with planning an economy were so complex that they could not be solved. It was claimed that, without the feedback mechanisms of the market, decision-making would be arbitrary and inefficient. So long as the Soviet economy had a rate of growth in excess of the West these ideas did not seem very plausible. But when that economy became more complex, and growth slowed, these criticisms seemed to gain relevance.

In his book The Economics of Feasible Socialism (1983), Alec Nove argued persuasively that if a planning agency, with all its access to national statistical data, cannot plan effectively, then it is even more hopeless for a collection of decentralized workers’ committees to do it. So are we left with no alternative to the market? Must we content ourselves with advocating worker shareholdings? We believe not. One of us is a computer scientist, and for the last few years has been researching the possibilities of using modern computers to solve planning problems.

We believe that it can now be conclusively demonstrated that the bourgeois arguments against socialist planning are outdated. 10 The problems of calculation that seemed daunting in the past can now be readily handled by powerful computers. Many people are now familiar with spreadsheet programs like Lotus-123 that are used on personal computers to prepare company plans. The problem of drawing up a plan for an economy can be thought of as a giant spreadsheet or matrix M. The rows of the spreadsheet represent the different economic activities, while the columns represent the products used by these activities. If the first row represented electricity production and the second represented oil production then M1,2 (row 1, column 2) would be the amount of oil used to produce electricity and M2,1 (row 2, column 1) the amount of electricity used to produce oil. The last column of the spreadsheet will hold the total amount produced by each process — so many terakilowatt hours of electricity and so many hundred million barrels of oil, etc. The bottom row of the spreadsheet shows the total inputs of each product used in all the production processes. The problem is to ensure that the total planned output of each product is at least equal to the total planned use of that product. What we know to start off with are the technical properties of the processes: One barrel of oil produces so many kilowatt hours. We also know the stocks of capital goods and means of production at the start of the year. What we must do is allocate these to different production processes in such a way as to meet the above constraints.

This is the problem of balancing the plan. In mathematical terms, it involves the solution of a very large number of simultaneous equations, perhaps 10 million equations if the plan is expressed in full detail. This task was quite beyond Gosplan, the Soviet central planning agency, but we have argued that it is now feasible in a matter of minutes or at worst hours — modest compared to the jobs run by physicists and weather forecasters. The two key requirements are (a) efficient algorithms and data-structures, and (b) current-generation high performance computers. The details of our case are spelled out in Cockshott and Cottrell (1993); Cottrell and Cockshott (1993a; 1993b). Gosplan, by contrast, was able to balance the Soviet plans only in highly aggregate terms; and as Nove (1983; 1986) has argued, this sort of exercise is never sufficient to ensure coherence where it matters, at the very specific level of particular goods.

In addition to producing a balanced plan, the optimization of an economy-wide plan is another highly computation-intensive task. The standard approach to this is to treat it as a linear programming problem. The planners specify a desired set of proportions for the outputs and, via the simplex method (see Bland, 1981), compute the allocation of means of production that will maximize the output, in those proportions. The problem with this approach is that the running time of an algorithm based on the simplex method can easily turn out to grow as the cube of the number of industries, or worse. Suppose the plan to be optimized deals with 100,000 distinct products. Then we are talking of some 1,000,000,000,000,000 computer instructions to solve the problem. On a 1960s computer the program would have taken some 30 years to run.11 Soviet economic planners resorted to running smaller linear programs, handling only a few hundred key products. At this size, the equations could be solved. This explains one of the strengths of the Russian economy. It did well on certain key projects, such as the space program, which could be given high priority in the planning process. But even today in the West there just is not the computer power available to apply the same techniques more widely.

One of the authors has developed an alternative plan-optimization algorithm, based on concepts from the field of artificial intelligence, whose computational demands are very much less than those of linear programming. The running time of this algorithm, described in detail in Cockshott (1990), is less than proportional to the square of the number of products, making it feasible for very large systems. It has been used to optimize the plan for a model economy of about 4,000 industries on a desktop computer (a Sun 3) in about five minutes. Unlike simplex, the alternative algorithm is not guaranteed to find the global maximum — but then, of course, neither is any market mechanism! There is no technical reason why the United States could not have a completely planned economy. Each workplace would have PCs linked to a network of computers within the enterprise which would in turn be linked to a continent-wide network of supercomputers.

The workplace would build up a local spreadsheet of its production capabilities and raw materials requirements. These would be trans- mitted through the hierarchy of machines which would balance up supplies and demands and draw up plans accordingly.

Using computer networks, rival teams of economists could present to the public several alternative continental plans each of which would provide full employment but be directed towards different ends: improving our public transport, investing more in industrial equipment, implementing energy-saving measures, improving housing conditions, etc. People could then vote at a referendum for whichever of these development plans they wanted, knowing that the various alternatives had been thoroughly costed and proved feasible.

5.1. Centralized or decentralized? Among economists hostile to central planning there is a belief that a system of distributed, decentralized decision making is bound to be superior to a centralized one. It is interesting to contrast this view with that taken by computer scientists and complexity theorists studying parallelism and optimization problems. In computing the presumption is the opposite: One tries first to solve problems using a single processor and only if this is impossible does one embark on the risky path of parallel or distributed processing. Experience has taught that solving problems in parallel is a great deal harder than it seems at first.

A distributed system of decision making, such as the market, might be superior to a centralized one on two distinct axes. It might be faster, and it might come up with better solutions to problems. It is often true that if more people work in parallel on something, they will finish the job faster. Often, but famously not always: Nine women don’t produce a baby in one month. More generally, whether parallelism is worthwhile depends on the ratio of work done to communication. Dividing up a decision-making task, whether on computers or among humans, soon results in a situation where most of the machines or people are waiting idly for input from their collaborators. Communication becomes the bottleneck (see, for instance, Stone, 1987, ch. 6). Generally, the further the messages have to go, and the more human intervention is needed to send a message, the slower the whole process becomes. In a market system, the sending of messages can be very slow, since one of the ways firms “communicate” is by altering the levels of their production, which may change the price level. Messages of this sort take months or years to send.

In a computerized system the same principles apply. Designers of fast machines try to bring all of their components as close together as possible. This limits the time that messages propagating at the speed of light will take to get from one part of the machine to another.

A distinct issue is whether the solution arrived at by parallel processes will be as close to optimal as that arrived at by a single process. The question arises because in parallel decision making each process makes decisions on the basis of out-of-date information about what other processes are doing. This is an inevitable consequence of communications delays.

In practical applications where parallelism cannot be avoided, such as distributed databases for airline bookings, considerable trouble has to be taken to ensure that the decision making processes have interlocks which make them, in principle, “serializable.” To ensure correct results, that is, one has to show that the parallel decision-making process is formally equivalent to a single serial process. In the absence of such interlocks, one could get the situation where two agents in distinct towns check if a seat is free. They may both be informed that it is. Each then books it and issues a ticket, and updates the database with the name of the passenger who has booked it. The end result is that two passengers are issued with tickets to the same seat, but only the name of one of them is entered in the database.

In the absence of such interlocks, the effectiveness of decision making can degrade massively. Macready, Siapas and Kauffman (1996) have shown that as one adds processors to an optimization problem, one initially finds that the solutions arrived at are marginally better than would be achieved using a single process. However, for any given complexity of problem one hits a distinct phase transition, beyond which the answers arrived at become very much worse than those produced by a single processor. The particular problem for which they have demonstrated this property is that of finding the minimum energy configuration for what is called a “spin glass.” A spin glass is a simplified model of interacting magnetic domains in the presence of an ambient field. The point almost certainly generalizes to economic problems because spin glasses are a simple paradigmatic example of optimization in interconnected systems, and such phase transitions seem to appear generally in massive decision and constraint satisfaction problems12.

5.2. Information overload. We claim that the coordination of social labor can be achieved more effectively via a system of planning. In advancing this claim we are obliged to meet the standard objection that socialist planning entails an enormous, suffocating bureaucratic apparatus, and that it must eventual choke under information overload (for instance, Hayek 1945; 1955). This myth has been repeated so often that it is believed even when the facts so evidently contradict it.

Taken literally, the word “bureaucracy” refers to those working in bureaus or offices. The observable fact about the socialist economies is that they employed far fewer people in bureaus or offices than capitalist economies at a comparable stage of development. Capitalist cities are high-rise, their skylines dominated by office tower blocks. Socialist cities were low-rise, dominated by the long sheds of industry. Material production, not information processing, dominated their economies. In fact it is capitalist economies that are dominated by, choked by, a constantly rising overhead of unproductive bureaucratic work, for what else is the banking, insurance, sales and marketing that fills the tower blocks?

The bureau was the manufactory of information processing, the locus of a formal subordination of information-processing labor. With its subdivision of mental labor it stands to information processing in the same relation as Adam Smith’s famous pin factory to material processing. The next stage in development — the real subordination of labor to machinery — is achieved first with the Hollerith tabulator and then with the computer center. What the self-acting mule was to material production, the Hollerith machine and IBM became to information processing.

Necessity is not the mother of invention, but of application. All of the essential ingredients of information technology were invented in the early 19th century. In their conceptual sophistication, computational power and engineering elegance, Babbage’s machines of the 1830s and 1840s put ENIAC and Colossus to shame. But despite generous state funding for their R&D there was no commercial need for them at the then current level of capitalist development. The technology was stillborn, forgotten until this century.

The initial impetus for rebirth came again from raisons d’état — the census for Hollerith and the tabulator, army ballistics for Mauchley and the ENIAC, intelligence gathering for Turing and the Colossus. But the impetus for their general application came from the information processing crisis of mid-20th century capitalism — the deluge of commercial correspondence, the truckloads of checks to be cleared daily. By analyzing the information-processing costs implicit in a market system in contrast to a centrally planned system, and examining the laws that govern how the respective costs grow as a function of the scale of the economy, one can both explain why the gathering and communication of information poses such a problem for mar- ket economies, and show why it was less of a problem for socialist ones. We cannot present this analysis here, but would refer the reader to Cockshott and Cottrell, forthcoming.

6. Conclusion

Marx’s critique of capitalism has two main aspects: Capitalism is unjust, being based on the exploitation of labor, and — although it was a tremendously progressive system relative to previous modes of production it is also inefficient, this inefficiency taking the forms of both the “anarchy” of the market and the systematic squandering of labor. We have attempted to outline a vision of a socialist system that answers both of these issues, using the Marxian labor theory of value as a basis. Our suggestions have, we trust, been bold and controversial. We believe it is better for socialists to be bold than to be timid. In this way socialist ideas present themselves with greater clarity and distinctness; and it should be noted that a bold redistri- bution of income, of the sort we have proposed via the labor-token system, stands to benefit far more people than a timid redistribution. We hope we have made the point that the labor theory of value, understood in a broad sense, provides a definite moral principle with which to oppose the market order. Lacking such a principle, socialists are reduced to tinkering at the margins, which will never fire the imagination of those who are oppressed and exploited in the present system.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Source:Science & Society,Vol. 61, No. 3 (Fall, 1997), pp. 330-357. Published by: Guilford Press. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40403641

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

[*] William Paul Cockshott is a Scottish computer scientist and political economist. He earned a PhD in Computer Science from Edinburgh University. In computing, he has worked on parallelism, 3D imaging, the limits of computability, video encoding, electronic voting and various special purposes computer designs. In political economy, he works on value theory, socialist planning theory and the econophysics models of production and money. His most recent books are Classical Econophysics (2009), with Allin F. Cottrell, Gregory G. Michaelson, Ian P. Wright and Victor M. Yakovenko; Arguments for Socialism (2012), with David Zachariah, and Computation and its Limits (2012). He is now an honourary research fellow at the University of Glasgow, having retired from teaching.

[*] Allin F. Cottrell is a Scottish political economist. He earned a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Edinburgh. He moved to the U.S.A. in 1983 and taught at UNC-Chapel Hill and Elon College before going to Wake Forest University, North Carolina, USA, in 1989. He is a professor in the Economics Department at Forest University ever since. Research interests include the history of economic thought (Marx and Keynes in particular), macroeconomics, and the theory of economic planning. His most recent books are Transition to 21st Century Socialism in the European Union (2010), with W. Paul Cockshott and Heinz Dieterich, and Gretl − Gnu Regression, Econometrics and Time-series (2016), with Riccardo Lucchetti.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

REFERENCES

Bland, Robert. 1981. “The Allocation of Resources by Linear Programming.” Scien- tific American, June.

Cockshott, W.Paul. 1990. “Application of Artificial Intelligence Techniques to Economic Planning.” Future Computer Systems, 2:4, 429-443.

Cockshott, W. Paul and Allin Cottrell. 1989. “Labour Value and Socialist Economic Calculation.” Economy and Society, 18 (February), 71-99.

———————————————— 1993. Towards a New Socialism. Nottingham, England: Spokesman.

———————————————— Forthcoming. “Information and Economics: A Critique of Hayek.” Research in Political Economy.

Cottrell, Allin and W. Paul Cockshott. 1993a. “Calculation, Complexity and Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Once Again.” Review of Political Economy, 5:2,73-112.

————————————————. 1993b. “Socialist Planning After the Collapse of the Soviet Union.” Revue Européene des Sciences Sociales, XXXI, 167-185.

Delphy, Christine. 1984. Close to Home: A Materialist Analysis of Women’s Oppression. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press.

Farjoun, Emmanuel and Moshe Machover. 1983. Laws of Chaos. London: Verso.

Hayek, Friedrich A. 1945. “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” American Economic Review, 35, 519-530.

———————— 1955. The Counter-Revolution of Science. New York: The Free Press.

Laibman, David. 1992. “Market and Plan: The Evolution of Socialist Social Structures in History and Theory.” Science & Society, 56:1, 60-91.

Macready, William G., Athanassios G. Siapas and Stuart A. Kauffman. 1996. “Criti- cality and Parallelism in Combinatorial Optimization.” Science, 271 (January 5), 56-58.

Marx, Karl. 1963 (1847). The Poverty of Philosophy. New York: International Publish- ers.

————— 1970 (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

—————1971a (1859). A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

—————1971b (1894). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume III. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

————— 1974. “Critique of the Gotha Programme.” In David Fernbach, ed., The First International and After (Political Writings, Volume 3). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin. ~

Moseley, Fred. 1991. The Falling Rate of Profit in the Postwar United States Economy. New York: Macmillan.

Nove, Alee. 1983. The Economics of Feasible Socialism. London: George Allen and Unwin.

————— 1986. The Soviet Economic System.Third edition. Boston, Massachusetts: Unwin Hyman.

Prosser, Patrick. 1996. “An Empirical Study of Phase Transitions in Binary Constraint Satisfaction Models.” Artificial Intelligence, 81:1-2 (March), 81-109.

Rodbertus, Karl. 1904. Das Kapital. Paris: Griard and Brière.

Smith, Adam. 1937 (1776). The Wealth of Nations. New York: The Modern Library.

Sraffa, Piero. 1960. Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Steedman, Ian. 1977. Marx after Sraffa. London: New Left Books.

Stone, Harold S. 1987. High Performance Computer Architecture. Reading, Massachu- setts: Addison Wesley.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

NOTES

- A fuller exposition of many of the ideas presented here may be found in our recent book, Towards a New Socialism (Cockshott and Cottrell, 1993).

- «Under the rural patriarchal system of production, when spinner and weaver lived under the same roof — the women of the family spinning and the men weaving, say for the requirements of the family — yarn and linen were social products and spinning and weaving social labor within the framework of the family. But their social character did not appear in the form of yarn becoming a universal equivalent for linen» (Marx, 1971a, 33). For a good analysis of this case see also Delphy, 1984.

- In the posthumously published volume III of Capital (Marx, 1971b), Marx qualified this with the idea that in a capitalist economy what he called “prices of production” operate. These prices involve goods whose production is capital intensive selling above their values. The theory of prices of production was further developed by the neo-Ricardian economist Sraffa (1960) and has been used by critics of Marx to try to invalidate his analysis of exploitation (Steedman, 1977). The theory of prices of production is premised on equality of rates of profit across branches of production. It has been demonstrated by Farjoun and Machover (1983) that this premise does not hold empirically, and that the predictions of the labor theory of value as described in Volume I of Capital offer a better approximation to reality.

- Karl Rodbertus, an influential socialist theorist of the 19th century, and founder along with Ferdinand Lassalle of “state socialism.”

- One of the criticisms that economic reformers leveled at the old price and wage structure in the USSR was that the low level of wages there led to this same sort of waste of labor. In the USSR wages were kept low and a significant part of people’s incomes came in the form of heavily subsidized housing and public services. In opposition, reformers advocated a change in the price and wage system so that services would cost more while wages would be raised to compensate. They claimed that the higher price of labor would then act as an incentive for innovation. The argument is valid, but does not go far enough. The problem arises because the wage —that is, the price paid for labor, rather than labor time itself — is used in costings.

- Marx was highly critical of Proudhon’s version of “labor-money,” as was Engels of Rodbertus’ version (see Marx, 1963, for both arguments). Their critiques focused on a specific issue: Proudhon and Rodbertus were mistaken in thinking one could introduce a system of pricing according to labor-time in the context ofa commodity-producing economy. But Marx advocated such a system for a planned, communist economy. Besides the passages cited above, the Critique of the Gotha Programme (Marx, 1974) gives a clear presentation of Marx’s own proposals. For an extended discussion of these points see Cottrell and Cockshott (1993a).

- «The annual labor of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes, and which consist always either in the immediate produce of that labor, or in what is purchased with that produce from other nations» — Adam Smith (Smith, 1937, lvii).

- «In a social state of this description» (i.e., a capitalist one), «people produce not with a view to satisfying the needs of labor, but the needs of possession; in other words, they produce for those who possess» (Rodbertus, 1904, 161).

- In normal commercial practice, entrepreneurs going into business decide on the selling price for their product by adding up the costs of wages plus raw materials and adding “normal” profits, all in money terms. They can determine the prices of raw materials from trade catalogs, and the wages they will have to pay by scanning the job adverts of the local paper. The equivalent calculations in terms of labor time are in principle even easier. If catalogs are published stating how much labor went into each raw material, then all that has to be done is add these costs in terms of indirect labor to the number of hours of direct labor used. None of this requires any computational technology unavailable in Marx’s day; ledgers, printed catalogs and clerks with training in arithmetic would have been enough. Today, of course it could be done using computer networks, which could put the catalogs on-line and update them daily. For an analysis of the computer resources needed see Cockshott and Cottrell, 1989.

- For a longer presentation of the argument see Cockshott, 1990; Cockshott and Cottrell, 1989; 1993.

- We mention a 1960s computer here because the mainframes available to the Soviet planners were mostly based on Western designs of this period.

- For another example of this sort of argument see Prosser, 1996.