After the financial crash of 2008, the ability of the ruling classes in the West to maintain a level of social compromise on the home front has been largely exhausted. As Wolfgang Streeck has argued,1 after the onset of the post-war crisis in the late 1960s, governments were still able to use inflation and debt to postpone the unravelling of the domestic social contract. Since 2008, these escape hatches have been closed. The scions of speculative finance, who paradoxically consolidated their directive role after the crash, have nothing to offer to the large mass of the population any longer. Whether or not in response to actual revolt (as in the French Yellow Vest movement), there is a manifest drift towards authoritarian government and a ‘politics of fear’. This has become the political formula, or ‘concept of control’, of what is best labelled predatory neoliberal capitalism.2

The Soviet bloc also showed the first signs of crisis in the late 1960s. By resorting to repression in response to the attempts in Czechoslovakia to adjust state socialism to a more advanced level of the productive forces, it revealed that the system had exhausted its potential for modernization other than backsliding to the market and capitalism (which had been one of the options in Czechoslovakia too, but not the only one). Even so, the USSR and its bloc did not collapse until the late 1980s, so the idea of socialism, its problems and possibilities, continued to be associated with Soviet state socialism for another twenty years. For at least a generation, the notion that we live in the era of the transition from capitalism to socialism went down with the lowering of the hammer and sickle flag on the Kremlin in 1991.

However, as I argue here, the development of the productive forces, the ‘limits of the possible’ in terms of social control of the forces of nature, in fact entered a new, revolutionary stage from around the time of the original crisis of the late 1960s. This stage can be brought under the heading of the Information Revolution, the application of information theories such as cybernetics in combination with advances in computer technology and digital communication networks, culminating in the Internet.3 Already under capitalist conditions this has resulted in a knowledge economy, or noönomy,4 but the social, auto-regulatory possibilities it opens up are bound to be incompatible with the private appropriation characteristic of capitalism.

Private versus Social

In the Grundrisse, the rough notes for Capital, Marx speculated how machines, fixed capital, would ultimately evolve into an automatic system.

The means of labour passes through different metamorphoses , whose culmination is the machine, or rather, an automatic system of machinery …, set in motion by an automaton, a moving power that moves itself. This automaton consisting of numerous mechanical and intellectual organs, so that the workers themselves are cast merely as its conscious linkages.5

Automated machinery represents social knowledge transformed into assets controlled by capital:

The accumulation of knowledge and of skill, of the general productive forces of the social brain, is thus absorbed into capital, as opposed to labour… In so far as machinery develops with the accumulation of society’s science, of productive force generally, general social labour presents itself not in labour but in capital.6

This sums up the contradiction we are experiencing today: the ‘social brain’ (roughly, the Internet) is collective, combined, social, but it is controlled by capital, i.e., a handful of large corporations such as the US Internet monopolies (Google, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon… ). These also serve as the eyes and ears of US and allied Anglophone intelligence, the ‘Five Eyes’, and are themselves interlocked with financial institutions such as BlackRock and the oligarchy they serve.7

The Information Revolution accelerated after the Nixon administration uncoupled the dollar from its gold cover, freeing itself from the need to balance the books as long as the world’s propertied classes were willing to bank on US economic and military might and the US currency remained the preferred means of payment in the world economy.8 This helped the IT sector to establish itself in the 1980s and 90s as an American phenomenon, Silicon Valley.9 Data-gathering for the intelligence agencies commissioning the research from which the big IT monopolies would emerge, early on created problems of storage, and it was not different for the fast rising financial sector. Even the largest mainframe computers could not handle the amount of data generated by innovations such as derivatives, securitization, and super-leveraging. In 1986, a company developing parallel database systems based on a cluster architecture, Teradata, delivered the first such system to the discount store turned shadow bank, Kmart.10

Today even Google, Facebook, Amazon, etc., and the surveillance state with which they are closely aligned, find it difficult to control the exponentially expanding amount of data. Stored in several thousands of commercial servers, Big Data are analysed through dedicated systems such as Google’s GFS, an expandable, distributed file system that supports large-scale, data-intensive applications.11 Even so the IT system owners do not have the Internet to themselves. Today, almost the entire population is connected one way or another, with even electricity-starved Africa catching up fast.12 This highlights the democratic potential of the Information Revolution, for whilst Internet and related technology ‘creates new capacities …, these new capacities may be more important for those that did not have them, than for those who already did.’13

Information, knowledge, is immediately social (one can, in principle, possess an item of information without somebody else being deprived of it), and only the capitalist regime, by attaching intellectual property rights to, say, new medicines, bars it from universal use.14 Objectively, ‘technically’, the new productive forces enable the world to move forward to a different, more humane type of society, but all kinds of stratagems are being developed to force them back into capitalist straitjacket. The 2009 World Economic Forum’s annual gathering at Davos presented a ‘New Deal on Data’, meant to turn those providing their information into active property owners. However, the allure of emancipation characteristic of so many aspects of the digital universe hides its exploitative thrust. Ubiquitous electronic networking dissolves the remaining barriers separating private life from work. Alongside flexible and freelance jobs, the ‘sharing economy’ in which every aspect of the personality and its possessions (bicycle, car, home…) is forcibly monetised, places the lower reaches of the labour market under the discipline of capital.15

Yet the notion that only the market can regulate a modern economy given its overwhelming complexity, ruling out planning (the thesis of neoliberal capitalism’s paramount ideologue, Friedrich Hayek), is beginning to wear thin in the age of Big Data.16 The choice between planning and freedom was always an ideological construct, floated by Hayek and other organic intellectuals of the financial asset-owning strata. Mono-centric efficiency and humanistic polycentrism can be mutually accommodated by democracy in a range of ways, as the Polish Marxist, Wlodzimierz Brus, already established in the early 1970s.17

A flexible, cybernetic system of central planning connected to digitalised individual preferences fed into the larger framework in the way supermarkets respond to customer demand, is one way of such a mutual accommodation. Or, in the words of Silicon Valley guru Tim O’Reilly, ‘We are at a unique time when new technologies make it possible to reduce the amount of regulation while actually increasing the amount of oversight and production of desirable outcomes’.18

How, then, can we ensure that in the current authoritarian conjuncture, such regulation can be democratised?

The Information Revolution in Historical Perspective

The Information Revolution, understood as the process ultimately leading to the universal, real-time interconnectedness of the entire population of Planet Earth, can be understood as the third great space/time compression in human history, comparable to the Industrial Revolution and further back, the Neolithic Revolution that brought us the domestication of plants and animals. One common element of the three qualitative leaps in how human communities utilise the sun’s energy, was that for obvious reasons, the initial advantages arising from them bolstered the existing ruling classes first. Yet both exchange advantages and/or war-making capacities in the sphere of foreign relations, and opportunities for exploitation in the sphere of production and reproduction, inevitably generated possibilities, mental and material, for subaltern forces as well. If we confine ourselves to the Industrial and the Information Revolutions, we can identify the key differences between the two socialisms I distinguish: what I call industrial labour socialism, and digital, Big Data eco-socialism.

The Industrial Revolution had its epicentre in Britain, mobilising the resources of its empire, human and material. In the Atlantic West arising from this mutation, capitalism was consolidated as the new mode of production, and sovereign equality as the ascendant mode of foreign relations. This allowed contender states resisting Anglophone supremacy, beginning with absolutist France, then Prussia-Germany, Japan, etc. to catch up industrially, and exposing the remaining land empires (China, Persia, the Ottoman empire) to the rule of the West.19

In the course of the century following the Industrial Revolution, labour socialism emerged as the internal subaltern force resisting it. The workers’ movement inspired by Marx and Engels and the First International they founded, was eventually destroyed in the First World War, but Soviet-style state socialism, forced back into an external contender posture facing the liberal capitalist heartland, replicated, successfully at first, the Industrial Revolution, as other contenders had done before it.

Today we are in the midst of another world-historic transformation, the Information Revolution. Externally, it pits the declining West, led by the United States, against a loose, largely involuntary contender bloc. Labelled the BRICS or otherwise, these are states such as China and Russia, in which capitalist restoration and/or neoliberal restructuring was followed by the discovery that they were not supposed to defend their sovereignty any longer and instead had to submit to Western global governance. So in the foreign relations domain, the new possibilities empower the West first and as long as it occupies the commanding heights of the geopolitical economy militarily and intelligence-wise, financially, and culturally, it retains the ability to strike whenever its hegemony is endangered. Systems not accessible to Five Eyes spying, such as those run by the Chinese IT giant Huawei, are attacked by all means available, from boycotts to hostage-taking, to keep this pre-eminence intact.20

Internally, the achievements of the Information Revolution are put to use for class oppression and heightened exploitation. Facial recognition coupled to round-the-clock observation of people give rise to potentially totalitarian control; in every segment of the wealth scale, ‘impersonal systems of discipline and control produce certain knowledge of human behaviour independent of consent’.21 A Swiss specialist in neuro-engineering, Marcello Ienca, reviewing the new departures into brain and identity manipulation by the large IT corporations, warns that the time in which they will be able to actually direct people’s preferences is not too far away any more. He argues for a ‘right to psychological continuity’ to prevent personality-changing interventions already being experimented with in the military.22

The new IT applications are not confined to the West, except that here, they play out in the context of a spiritual crisis arising from the erosion of life chances for the large mass of the population. Austerity to combat irredeemable indebtedness and financial irresponsibility, festering wars and mass migration, fuel new superstitions and a rise of superficiality and vulgarity in popular culture. The Internet, Marx’s ‘social brain’, like any biological brain, is also the repository of much that we would not normally see fit to express openly. Yet under cover of anonymity, ‘DonaldDuck2’ and his fellows have no qualms going ever further in depravity, creating a downward spiral in which a new generation of populist politicians cater to their instincts, further changing the signposts, and so on. Can this be the social material with which a new, democratic and ecologically friendly socialism will be erected?

The former socialist states forced back into a contender role in spite of their conversion to capitalism, such as China or Russia, have so far not been able to develop alternative, cohesive world views and ways of life sufficiently attractive to claim hegemonic status. Whilst maintaining a measure of state direction and protection, they also remain exposed to both neoliberal doctrine and Western popular culture undermining their defence of sovereignty.

The Information Revolution, then, has created a situation in which once again, the new possibilities in principle empower the Western ruling classes first — but both on the foreign relations and the relations of production dimensions, their ability to really impose the neoliberal regime is compromised. To steer humanity clear of a full-scale central war and irreversible destruction of the biosphere, it is therefore urgent that the IT infrastructure is made transparent and placed under some form of democratic control. So far all attempts to transfer governance of the Internet and World-Wide Web to multilateral bodies, even after the Snowden revelations about global surveillance by the Five Eyes, were effectively sabotaged by the US, the EU, and the private body assigning domain names, ICANN, domiciled in California.23 On the other hand, the fact that the capitalist ‘noönomy’ has become entirely dependent on IT — through the Internet of Things, intelligent machines linked to the ‘social brain’, or otherwise—rules out that it would be switched off for political reasons other than temporarily and locally. So in a way, the accessibility of the Internet is guaranteed by the fact that it has meanwhile become indispensable for the operation of the economy as well.

So how can we expect that progressive forces would be able to disentangle themselves from this mutual embrace, and obtain democratic transparency? This in my view depends on the economic prospects of speculative capital, the social force guiding the West. Barring a resort to all-out war, a new collapse of the 2008 type would accelerate the transition towards a new, ‘associated’ mode of production that has matured within the old one, which itself has been brought to ruin by predatory finance.24 That the IT infrastructure for a 21st-century socialism is largely in place, is a crucial factor here, although not entirely new either. In the Russian Revolution too there were structures that could be taken over intact, but they did not go beyond state control (of the war economy).25 This state degenerated into the party-police state under Stalin, but eventually was able to resurrect its socialist antecedents and among many other legacies, left us the experiments with digital planning that continue to be relevant today.

Soviet Planning: Command Economy and Digital Departures

Soviet (state) socialism crystallised in the failed world revolution of 1917-’24. In hindsight this marks the moment when the internal challenge arising from the Industrial Revolution, labour socialism, became secondary to an external one, a contender state resisting Western imperialism. The command economy that was instituted under the Five-Year Plans in the late 1920s relied on (initially extreme) coercion to compensate for Russia’s backwardness, and ultimately allowed the USSR to defeat the Nazi invaders. In the 1960s, when growth began to slow down after the initial breakneck industrialisation, a digital transformation was considered as a way out. Some of its achievements were far ahead of their time and herald our current epoch, even though they ultimately ran into a conservative response blocking their revolutionary potential.

Computer design began at the Academy of Sciences in Kiev in the 1940s. Military applications were a priority and when they learned about the computerised air-defence system being developed in the United States, the Soviet leadership wanted to respond by a comparable system of their own. The first book in Russian dealing with computers, Electronic Digital Machines, was written by Anatoliy I. Kitov, a colonel engineer in the armed forces of the USSR.26

Ideological barriers to theories such as cybernetics, needed for the effective use of electronic devices, were only lifted after Stalin’s death. Party leader Nikita Khrushchev in his speech at the XXth Party Congress in 1956, in which he denounced Stalinism, also advocated steps to introduce factory automation. Kitov then proposed making the envisaged air defence network available for civilian uses in peacetime; but he by-passed the military hierarchy by addressing Khrushchev directly and was stripped of his rank and also expelled from the party. The idea of digitalising the command economy remained alive, even though a school advocating profitability as the lever for efficiency also emerged, led by E. Liberman.27

At the Twenty-Second Party Congress of 1961, Khrushchev again declared it imperative to accelerate the application of digital technologies to the planned economy.28 In this period, following the Sputnik space successes, the enthusiasm about the USSR overtaking the West was at its height and cybernetic economic management was a key component of the fervour. A report for the Council of Foreign Relations in the United States noted that Soviet planners saw cybernetics as the most effective instrument for ‘the rationalisation of human activity in a complex industrial society’.29 The Soviet press began popularising the idea of computers as the ‘machines of communism’, causing US observers to consider that ‘if any country were to achieve a completely integrated and controlled economy in which “cybernetic” principles were applied to achieve various goals, the Soviet Union would be ahead of the United States in reaching such a state’.30 The CIA published a series of reports in which the agency expanded on this theme, warning in particular that the USSR might be on the way to building a ‘unified information net’ that in the eyes of some of president Kennedy’s advisers would, if successful, ‘bury the United States’ as Khrushchev had promised.31

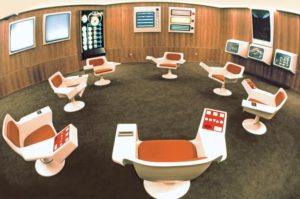

Viktor M. Glushkov, the director of the Computing Centre of the Academy of Sciences of Soviet Ukraine, at this point conceived the Nation-wide Automated Economics Control System (in Russian, OGAS), actually hiring the disgraced Kitov as his assistant.32 Alexei Kosygin, then deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers, encouraged Glushkov to elaborate his ideas about digitalising the planning system. However, in 1964, when a comprehensive digital plan blueprint was finally submitted, Khrushchev was sidelined by the combined forces of conservatism and caution. The new leadership under Leonid Brezhnev (and with Kosygin as prime minister) opted for greater enterprise autonomy along the lines of Liberman, accepting that the last thing local bosses wanted, was to have all their assets and activities digitally recorded by the centre.33

On a parallel track, Kosygin was engaged in striking large-scale deals with Western European companies in order to modernise the Soviet economy. His son-in-law, Dzhermen Gvishiani, would fashion the Soviet response to the American plan to launch a joint think-tank to deal with problems of advanced industrial society. Out of this would emerge the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna, in which Gvishiani held the top position on the Soviet side until 1986.34

From the West, IIASA was perceived as a means of subverting Soviet state socialism, and after the neoliberal turn under Thatcher and Reagan, Anglo-US support for the institute was in fact terminated. As we can now see, this also interrupted a transnational process of class formation of a forward-looking managerial cadre, that is, specialists typically inclined to systems thinking and interested in problems transcending the East-West divide.35 The mathematical global modelling developed at IIASA, at the UN, and for the Club of Rome (in which Gvishiani was involved since his first meetings with the heads of Olivetti, FIAT, and other pioneers of East-West trade, who set it up), was used to address issues such as raw material use as well as atmospheric and oceanic pollution.36

With Glushkov, Nikita Moiseev (the mathematician and head of the Soviet Academy of Sciences’ Computer Centre in Moscow, who revived interest in the 1920s biosphere theory of V.I. Vernadsky), and others, work on environmental systems struck deep roots in the USSR. In close collaboration with US scientists such as Carl Sagan, concerned about the cavalier attitude of the Reagan administration regarding nuclear war, this culminated in a joint US-Soviet report on the danger of nuclear winter.37 By applying complexity theory to the biosphere, it was found that the extinction of life on the planet by a full-scale nuclear exchange might equally come about by systemic changes in the Earth’s biosphere, and not even slowly, but potentially by a comparable, sudden catastrophe.38

The sort of planning that emerged from this experience is qualitatively different from planning the command economy by which a contender state pursues a catch-up industrialisation. Indeed ‘digital planning’ is not just planning with the aid of computers, but feeding vast amounts of, eventually, Big Data, into computer systems and discovering rather than dictating outcomes, as we are witnessing today with climate predictions — including the uncertainties that come with them. The Gorbachev leadership was guided by these notions, but it arrived too late to transform the social structures of the command economy to a digital planning format, and went under with the USSR and the Soviet bloc. Thus the visionary departures in the direction of digital planning were buried in the one type of society that had the social structures for it to succeed.39

A second experiment with digital planning occurred in Chile under Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular government. Here the element of cybernetic adjustment, including responsiveness to supply issues and strikes was explicitly accounted for, but it was cut short by the Pinochet coup in 1973. Stafford Beer, who had been brought in to head Chile’s Cybersyn project, shared the progressive managerialism of the IIASA/ UN/Club of Rome cadre, but he was kept out of IIASA to protect the institute’s non-political format. His Chilean deputy, Raúl Espejo, narrowly escaped the clutches of the US-backed terror regime.40 This takes us to the issue of the subject of a resumption of the project of digital planning today.

Who Will Bring About Regime Change?

The process of class formation of a progressive managerial cadre, pushed towards the Left by working class militancy in the 1960s and 70s, was interrupted by the neoliberal counterrevolution. Closing the era of post-war, broad class compromise, the resurgent capitalist class instead struck a more restricted deal with the upper layers of management and with asset-owning middle classes, whilst attacking the working class and progressive forces across the globe.41 Certainly one cohort of the IT cadre in Silicon Valley still shared the idea of Steve Jobs of Apple that the personal computer was an instrument of emancipation, but this 1960s outlook was soon turned into a libertarian, right-wing direction, ‘using cybernetic ideals of the counterculture to sell corporate politics as a revolutionary act’.42

Whether the privileged cadre will be inclined to follow the lead of the mass insurrections currently taking place in France, Chile, and elsewhere, may depend on the mobilisation of those educated for a cadre role but un- or underemployed in the current crisis, and sharing the fate of the lower classes finding themselves excluded.43

As Bukharin already wrote at the time of the Russian Revolution, for the cadre to give up their privileged position will be a tortuous process because it can only occupy such a position in capitalism.44 So how would their orientation converge once again with the outlook of the popular masses? Here the French Situationist philosopher, Guy Debord, provided important clues in the late 1960s. A key organic intellectual of progressive class formation of that period, Debord in his manifesto, The Society of the Spectacle, argued that unlike the bourgeoisie, which came to power as the ‘class of the economy’, of economic development (against the low-productivity, stagnant manorial economy of late feudalism), the ‘proletariat’ in the sense of the class that has no enduring stake in existing society, will stand little chance to out-compete the rapacious dynamism of capital. Labour socialism, and state socialism as its ultimate historic embodiment, found this out the hard way.

According to Debord, then, the progressive forces can only be superior to the bourgeoisie on the basis of their ability to look beyond the capitalist horizon, as a ‘class of consciousness’. 45 This consciousness will crucially include concern for the maintenance, indeed recovery of the biosphere, something largely absent from labour socialism, since in the spirit of the Industrial Revolution, its overriding idea was that progress was based on the conquest and exploitation of nature.

As far as actual production goes, already today, the IT infrastructure in principle ‘enables people to depart from immediate involvement in material production while remaining its “controllers and regulators’.46 This confirms Marx’s assessment of a future economy as ‘an automaton, a moving power that moves itself’, in which workers are merely the conscious linkages. In a Big Data socialism, we must expect this ‘collective worker’ of engineers-controllers to take the place of the capitalist oligarchy and reorient strategic decisions from private profit to the survival concerns of humanity. ‘Labour’ will be about performing the remaining creative tasks, whilst repetitive tasks that we associate with the ‘automaton’ will be left to algorithmic regulation.47

Now the consciousness disseminated through the Internet is a far cry from, say, the Marxism embraced by the industrial proletariat of the 19th, early 20th century. Far from being a corrective to ideological distortion, the Web itself is the key channel for the spread of misanthropic racism, climate change denial, and other abominations. However, the real movement is always the determinant of the flow of ideas, not the other way around. The epochal revelations of Manning, Assange and Snowden, which have no equivalent in the opposite camp, resonate in the many quality websites and remaining Left print publications that share the spirit of these persecuted champions of transparency. One may also put it this way: if what progressive channels publicise, would not be superior to fake news and hatred (in the sense that revolutionary Marxism was intellectually superior to the chauvinist militarism that led Europe into World War I), a revolution would deserve to fail — just as the Stalinist regression to mechanical materialism was a major factor in the demise of Soviet state socialism.

How a transition towards a situation in which society governs the economy rather than the other way around, is not a matter that can be predicted in detail. The geopolitical divide between the capitalist Atlantic heartland and the contender sphere outside it, would again be a major modifying factor, as in all modern revolutions.48 It is enough to establish that all elements for a world-historical transformation are in place; the transition hinges on how states will respond to pressures to ensure the security (job, food, energy security and the like) of the population under conditions of extreme financial volatility. Inevitably, the state will then take precedence over the IT monopolies. ‘Just as companies like Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon build regulatory mechanisms to manage their platforms, government exists as a platform to ensure the success of our society, and that platform needs to be well regulated’.49 Whether that will take the form of enlightened despotism or democracy, and what form democracy will take in turn, will be decided in real struggles.

For one, it will be essential that movements making demands on capital and the state also demand that control facilities embedded in data systems are publicly accessible. The (anonymous) metadata now in the hands of the large IT monopolies and dedicated companies like Palantir, and also of Airbnb, Uber, hospitals and insurance companies, should be made available to citizens, city and national government, and science, as part of a shift to democratic self-regulation.50 The Open Data movement, of which Aaron Swartz was an iconic figure (he took his own life when faced with a draconian sentence in the US for making privately copyrighted academic materials publicly accessible), seeks to create a data universe parallel to the Big Data available to the corporate sector, ‘civic data’. Indeed it has been argued that the ubiquity of data itself already works to generate a culture that is moving away from the bourgeois one of possessive individualism, or any other individualism irresponsible towards the larger questions of human survival. The availability of these data create expectations and habits that help build a civic culture which is resistant to corporate control.51

This new political culture would then interact with the shift in the operation of representative organs, from the United Nations and its functional and regional organisations down to national and sub-national parliaments and councils. As more and more issues concerning the organisation of the economy and the safeguarding of the biosphere including human health will be reclaimed for democratic decision-making, these bodies will again begin to attract quality memberships. After all, the decline of representative organs has everything to do with the fact that in neoliberal capitalism the strategic decisions are made by the oligarchies organised in (trans-) national planning bodies closely aligned with the major banks and corporations.52 Through the IT infrastructure, old ideals such as the right to recall of elected officials are becoming a reality because citizens will be provided with real-time information on how representatives vote. In combination with freely accessible tax data and data on secondary occupations of representatives, these are issues that will play a role in the transition already and people can be mobilised for them without having to sign up for epochal transformations that nobody can entirely be confident about.

What distinguishes a 21st-century Big Data socialism, from state socialism grafted on the industrial labour movement of the 19th and 20th, is that it would not be a ‘willed’ utopia. Only when a majority wants change to adjust the social order to possibilities that are obvious to all, will a revolution be able to assume a democratic format. ‘A determinate class will undertake the general emancipation of society starting from its particular situation, Marx wrote in 1844. ‘This class emancipates the whole society, but only on the condition that the whole society finds itself in the same situation as this class’[emphasis added]53 The original labour movement never faced the situation in which this would have applied; hence the need for a tightly organised party to lead the masses, impose and consolidate socialism by coercion, and so on. In the Information Revolution it is different: no other-worldly, exotic experiment here, because everybody is ‘connected’ or will be soon, and issues concerning the refashioning of the political order can be discussed with reference to a reality that is there for all to see. Certainly it would at some point require the expropriation of large private concerns, ideally beginning with the media, in order to make meaningful public discussion possible.

In this way the aforementioned structures of public representation, subject to digital transparency, may be expected to begin to set socialist targets beyond the day-to-day management of current affairs. These would ideally include,54

- A general rise in the cultural level and living standards, focused especially on the working class and other disadvantaged groups;

- A long-term resource-constrained pattern of development respecting the biosphere;

- Real economic equality between the sexes;

- The disappearance of all forms of distinctions of class, including the one between town and country.

Within these broad parameters of a reorientation of society as a whole, specific digital regulation would require four further steps: 1) an understanding of the desired outcome; 2) ‘real-time measurement whether that outcome is being achieved’; 3) algorithms (ordering rules meant to allow adjustment on the basis of new data), and 4) ‘Periodic, deeper analysis of whether the algorithms themselves are correct and performing as expected’.55

Summing up, a comprehensive, democratically controlled. ecologically secured, and digital planned economy is no longer a utopian ideology that requires a vanguard of trained revolutionaries to be imposed on a different reality, as in the case of labour socialism (certainly in countries such as pre-industrial Russia or China). The digital infrastructure is a democracy waiting to be turned into functioning social order. It lays the foundation for an appropriate political superstructure and practice that is not experienced as being led by ideological considerations in which one must believe, even when contradicted by reality. Instead it will rely primarily on hegemony, consensual rule as a permanent condition.

The idea that hegemony is about education, one of Gramsci’s key tenets, comes into play here. Education is not a matter of representation of an existing state of affairs waiting out there, which education informs us about, but a route to a reality in the making. Given that in the digital economy, algorithmic regulation reduces the burden of compulsory toil ever-faster, people’s time will increasingly be available for cultural enrichment and technological re-training. Thus education becomes the primary reproductive structure of society, instead of the economy which is largely automated and no longer provides the satisfaction of the original work experience.56

Democracy, then, is contemporary to the transition itself, rather than postponed as a matter to be solved ‘later’ as was the case with labour socialism. It will inevitably take on new and unforeseen implications and associations, in the way soviets emerged in 1905. Whether there will be coercive aspects of the transformation, given its regionally and internationally uneven progress, is something that cannot be excluded; however, digital transparency will also help to prevent consolidation of the power of those entrusted with these tasks.

To repeat: the key aspect of a transition to a Big Data socialism is that the IT infrastructure and the ability of people to think in terms of its possibilities (something that a new financial crash will only make more acute) are in place in principle. They are coming more into conflict with the oligarchic trend of contemporary capitalism and state repression with every passing day. A digital socialism will build on much that is already familiar, it will also underline the old ‘reformist’ tenet that socialism is not the negation of liberal capitalism, but transcendence in the sense of negation and continuation, the further development of tendencies already working within capitalism.

There is no point in further detailing the wish list of an imaginary digital socialism beyond the above. It suffices to establish that if capitalism, which is exhausting society and nature alike, is left unchecked, it will inevitably develop into fascism again, since it cannot bring forth a broad social consensus any longer, or accept compromise in foreign relations. Financial predation, the round-the-clock assault on nature and the threat of war do not leave us any choice but to engage in an urgent debate on how a different society might be achieved.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Source: This article has been published originally in Monthly Review, Volume 71, Issue 11 (April 2020). It is based on talks given by the author in May 2018 in Moscow, October 2018 in Cambridge, and in December 2019 at Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, and China University of Politics and Law, Beijing.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

[*] Kees van der Pilj holds a Ph.D. in Social Sciences from the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. He is a retired professor who used to teach international relations at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom. He lives in Amsterdam. His most recents books are Flight MH17, Ukraine and the New Cold War. Prism of Disaster (Manchester University Press, 2018), translated into German, Russian ad Portuguese, and The Discipline of Western Supremacy. Vol.III of Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy (Pluto Press, 2014). He is currently preparing several books, including Big Data Socialism. The Digital Planned Economy and Who Will Get Us There.

[*] Kees van der Pilj holds a Ph.D. in Social Sciences from the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. He is a retired professor who used to teach international relations at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom. He lives in Amsterdam. His most recents books are Flight MH17, Ukraine and the New Cold War. Prism of Disaster (Manchester University Press, 2018), translated into German, Russian ad Portuguese, and The Discipline of Western Supremacy. Vol.III of Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy (Pluto Press, 2014). He is currently preparing several books, including Big Data Socialism. The Digital Planned Economy and Who Will Get Us There.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Notes

- Wolfgang Streeck, Gekaufte Zeit. Die vertagte Krise des demokratischen Kapitalismus [Frankfurter Adorno-Vorlesungen 2012]. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2013.

- See my ‘A Transnational Class Analysis of the Current Crisis’, in Bob Jessop and Henk Overbeek, eds. Transnational Capital and Class Fractions. The Amsterdam School Perspective Reconsidered[foreword, Gerd Junne]. London: Routledge 2019.

- Evgeny Morozov, ‘Socialize the Data Centres!’ (interview). New Left Review, 2nd series (91), 2015, p. 57.

- Sergey Bodrunov, Noönomy. English version of Russian edition, presented at the Cambridge-St. Petersburg colloquium ‘Marx in a high technology era: globalisation, capital and class’. Cambridge, October 2018.

- Karl Marx, Grundrisse, Foundations of the Critique of the Political Economy. Rough Draft [trans. & intro, M. Nicolaus]. Harmondsworth: Penguin , 1973 [1857-‘58], p. 692.

- Ibid., p. 694, emphasis added.

- Glenn Greenwald, No Place to Hide. Edward Snowden, the NSA and the Surveillance State. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2014; Peter Phillips, Giants. The Global Power Elite [foreword W.I. Robinson]. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2018.

- Duccio Bassosi, Il governo del dollaro. Interdipendenza economica e potere statunitense negli anni di Richard Nixon (1969-1973). Florence: Polistampa, 2006, p. 34.

- Paul. Boccara, Transformations et crise du capitalisme mondialisé. Quelle alternative ? Pantin: Le Temps des Cérises, 2008, pp, 80, 88.

- James Jorgensen, Money Shock. Ten Ways the Financial Marketplace is Transforming Our Lives. New York: American Management Association, 1986, pp. 95-6; Chen Min, Mao Shiwen, and Liu Yunhao,‘Big Data: A Survey’. Mobile Network Applications, 19, 2014, p. 174.

- Chen et al., ‘Big Data: A Survey’, p. 186.

- Nick Dyer-Witheford, Cyber-Proletariat. Global Labour in the Digital Vortex. London: Pluto Press and Toronto: Between the Lines, 2015, p. 103.

- Michel Bauwens, Vasilis Kostakis, and Alex Pazaitis, Peer to Peer: The Commons Manifesto. London: University of Westminster Press, 2019, pp. 33-4.

- Christopher May, Global Political Economy of Intellectual Property Rights. The New Enclosures?London: Routledge, 2000.

- Timo Daum, Das Kapital sind wir. Zur Kritik der digitalen Ökonomie. Hamburg: Nautilus, 2017, pp. 183-4.

- Shoshana Zuboff, ‘Big Other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization’. Journal of Information Technology, 30, 2015, p. 78.

- Wlodzimierz.Brus, Sozialisierung und politisches System [trans. E. Werfel]. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.1975, pp. 192-3.

- Tim O’Reilly, ‘Open Data and Algorithmic Regulation’. In Brett Goldstein (ed. with Lauren Dyson). Beyond Transparency: Open Data and the Future of Civic Innovation. San Francisco, Cal.: Code for America Press, 2013, p. 293.

- See my Transnational Classes and International Relations, London: Routledge, 1998.

- Voltaire Network, ‘Five Eyes Against Huawei’. (7 December 2018). http://www.voltairenet.org/article204264. html (last accessed 16 December 2018).

- Zuboff, ‘Big Other’, p. 81.

- Marcello Ienca, ‘Do We Have a Right to Mental Privacy and Cognitive Liberty?’ Scientific American, 30 July 2017. https://blogs. scientificamerican.com/observations/do-we-have-a-right-to-mental-privacy-and-cognitive-liberty/ (last accessed 30 July 2019).

- Prabir Purkayashta and Rishab Bailey, ‘U.S. Control of the Internet. Problems Facing the Movement to International Governance’. Monthly Review, 66 (3) 2014, pp. 114, 118-9.

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, vol. III, Marx-Engels Werke, Berlin: Dietz, 1965, vol. 25, p. 456.

- V. I. Lenin, The Impending Catastrophe and How to Combat it [1917] in Collected Works, Moscow: Progress, 1972, vol. 25

- Benjamin Peters, ‘Normalizing Soviet Cybernetics’. Information & Culture: A Journal of History, 47 (2) 2012, pp. 169-70, 154.

- Slava Gerovitch, ‘InterNyet: why the Soviet Union did not build a nationwide computer network’. History and Technology, 24 (4) 2008, pp. 338-40;.Evsej G. Liberman, Methoden der Wirtschaftslenkung im Sozialismus. Ein Versuch über die Stimulierung der gesellschaftlichen Produktion [trans. E. Werfel]. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp,1974 [1970], p. 11.

- Peters, ‘Normalizing Soviet Cybernetics’, p. 164.

- Cited in Alexander Vucinich,, ‘Science’, in Allen Kassof, ed. Prospects for Soviet Society. New York: Praeger, for the Council on Foreign Relations, 1968, pp. 319-20.

- Gerovitch, ‘InterNyet’, pp. 335-6;.

- Ibid.; Peters, ‘Normalizing Soviet Cybernetics’, p. 165.

- Ukrainian Computing,‘Academician Glushkov’s “Life Work”.’ http://uacomputing.com/ stories/ ogas/ 2012 (last accessed 20 December 2018).

- Michael A Lebowitz,. The Contradictions of Real Socialism. The Conductor and the Conducted. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012, pp. 118-9; Gerovitch, ‘InterNyet’, p. 343.

- Eglė Rindzevičiūtė, The Power of Systems (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016) 44, 48, 69.

- See my Transnational Classes, chapter 5, ‘Cadres and the classless society’.

- Eglė Rindzevičiūtė, The Power of Systems. How Policy Sciences Opened Up the Cold War World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. 2016, pp. 44, 48, 69, & passim.

- Robert Scheer, With Enough Shovels. Reagan, Bush, and Nuclear War. New York: Random House 1982; John Bellamy Foster, ‘Late Soviet Ecology and the Planetary Crisis’, Monthly Review, 67 (2) 2015, pp. 9-11.

- William Rees, ‘Scale, complexity and the conundrum of sustainability’. In M. Kenny and J. Meadowcroft, eds. Planning Sustainability. London: Routledge, 1999, pp. 109-10; Georgi Golitsyn and Aleksandr Ginzburg, ‘Natural analogs of a nuclear catastrophe.’ In Y. Velikhov, ed. The Night After … Climatic and biological consequences of a nuclear war [trans.A. Rosenzweig, Y. Taube]. Moscow: Mir Publishers, 1985.

- Manuel Castells, End of Millennium [vol. III of The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture]. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell., 1998, pp. 47-56.

- Katharina Loeber, ‘Big Data, Algorithmic Regulation, and the History of the Cybersyn Project in Chile, 1971–1973’. Social Sciences, 7 (65) 2018, doi:10.3390/socsci7040065, pp. 1-15; Rindzevičiūtė, The Power of Systems, pp. 71-2. Espejo is currently president of the World Organization of Systems and Cybernetics, WOSC.

- Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy, ‘Neo-Liberal Dynamics—Towards a New Phase?’ in K. van der Pijl, L. Assassi, and D. Wigan, eds. Global Regulation. Managing Crises After the Imperial Turn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004, p. 30, and their Au-delà du capitalisme? Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 199

- Yasha Levine, Surveillance Valley. The Secret Military History of the Internet. New York: Public Affairs, 2018, p. 136.

- Jean-Claude Paye, ‘The Yellow Vests in France. People or Proletariat?’ Monthly Review, 71 (2); Christophe Guilluy, La France périphérique. Comment on a sacrificié les classes populaires. Paris: Flammarion, 2015

- Nicolas Boukharine,Économique de la periode de transition. Théorie générale des processus de transformation [trans. E. Zarzycka-Berard, J.-M. Brohm, Intro, P. Naville]. Paris: Études et Documentation Internationalres, 1976 [1920], p. 104.

- Guy Debord, La société du spectacle. Paris: Gallimard, 1992 [1967], p. 82.

- Bodrunov, Noönomy, pp. 158-9.

- Alan Freeman, ‘Twilight of the Machinocrats: Creative Industries, Design, and the Future of Human Labour.’ In Kees van der Pijl, ed., Handbook of the International Political Economy of Production. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2015; Daum, Das Kapital sind wir, pp., 60-66. The notion of the collective worker was developed by Marx in the unpublished sixth chapter of Capital, here cited from Un chapitre inédit du Capital [intro. and trans. R. Dangeville]. Paris: Ed. Générales 10/18, 1971.

- Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Out of Revolution. Autobiography of Western Man [intro. H.J. Berman]. Providence, RI: Berg, 1993 [1938].

- O’Reilly, ‘Open Data and Algorithmic Regulation’, p. 292.

- Daum, Das Kapital sind wir, p. 149.

- Eric Gordon and Jessica Baldwin-Philippi, ‘Making a Habit Out of Engagement: How the Culture of Open Data Is Reframing Civic Life’. In Goldstein, Beyond Transparency, pp. 139-40.

- William K. Carroll, The Making of a Transnational Capitalist Class. Corporate Power in the Twenty-First Century. [with C. Carson, M. Fennema, E. Heemskerk, and J.P. Sapinski]. London: Zed Press, 2010.

- Karl Marx, ‘Zur Kritik des Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie. Einleitung’ [1844], Marx-Engels Werke, vol. 1, p. 388.

- W. Paul Cockshott, and Allin Cottrell, Towards a New Socialism. Nottingham: Spokesman Books [pdf edition].1993, pp. 57-8.

- O’Reilly, ‘Open Data and Algorithmic Regulation’, pp. 289-90.

- See Boccara, Transformations et crise du capitalisme, and his .Une sécurité d’emploi ou de formation. Pour une construction révolutionnaire de dépassement contre le chômage. Pantin : Le Temps des Cérises, 2002.