Abstract

Cooperativism or socialism or communism (I am using these words interchangeably) requires, in addition to two other preconditions (one economic and one political), a definite stage of development of technology. This stage was only reached at the end of the 20th century with the synergetic convergence of several technologies: one-dimensional and two-dimensional barcodes, Internet, smartphones (2G, 3G, 4G, 5G), electronic payment cards, supercomputers, and Big Data (giant databases). Drawing upon these material artifacts, this paper outlines a technological criterion for screening proposals for what type of institutions a future socialist/communist/ cooperative society could have, identifying those that can guide not only the economy but also the decision-making process across all branches of government, in the traditional trifurcated sense of the term — executive, legislative, judicial. Let us call that criterion the beneficent principle (BP for short).

Key words: technology, beyond global capitalism, first stage of socialism.

1.The motivation for this paper

The motivation for this article was a diatribe by a defunct economist.1 I am talking about Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973), the famous Austrian economist, staunch defender of anti-Keynesian capitalism, and smart foe of socialism.

In the preface to the second German edition (1932) of his book, Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis (1922, 1932, 1936, 1951, 1959, 1981), Mises claims that socialists have no agreed solution to «the problem of how a socialistic society could function». Each socialist group, each socialist party, has its own private answer to this problem. «Each group of the great socialist movement claims its own as the only true brand and regards the others as heretical; and naturally tries to stress the difference between its own particular ideal and those of other parties». They do not care about this disagreement, because each of them is utterly convinced that they alone will be the leaders of the working class who, once in power, will decide what to do to establish socialism. «They assert that their particular brand of Socialism is the only true one — that which “shall” come, bringing with it happiness and contentment. The socialism of others, they say, has not the genuine class-origin of their own».

This is, let us face it, a fair portrayal of socialists and communists from the Gotha congress of the German socialist labour party [Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, SAPD], in 1875, to the present day. 2

Now, why is this so? Mises has his own answer. He suggests that the culprit is Karl Marx. According to Mises, it was ruled by Marx and his friend, Friedrich Engels, that no one «should be allowed to put forward, as the Utopians had done, any definite proposals for the construction of the Socialist Promised Land.» «Since the coming of Socialism was inevitable, Science would best renounce all attempt to determine its nature». And the irony of ironies, Mises adds, is that this ban on any scientific inquiry into the institutions and working of the socialist society of the post-capitalist future, has been labelled “scientific socialism.”

Mises is not clear about the connexion between his two claims: (i) the proliferation of different conceptions about the socialist mode of production and the socialist society, and (ii) Marx’s alleged ban on inquiring into that matter. But it is possible to reconstruct his argument as follows:

“Being the most sagacious critic of capitalism and the most articulate defender of socialism, Marx, nevertheless, ruled as unscientific any thorough investigation of the economic characteristics of the socialist mode of production and the institutional design of a socialist or communist or cooperative society. In so doing, he inadvertently opened the door to the cacophony of different proposals about the post-capitalist future advocated by his self-proclaimed followers” 3

Mises’ argument is not valid because one of its premises is false. There has never been any ban whatsoever by Marx or Engels about launching any scientific inquiry into the institutions and working of the socialist society of the post-capitalist future. This alleged ban is pure Mises’ invention.

But two facts remain. First, Marx did not put forward – for good reasons, as we shall see in sections 4 and 8 – detailed proposals about post-capitalist socialism or communism (I am using these terms interchangeably), a form of society that did not yet exist, and which still does not exist. He was only willing to give sketchy outlines – and, again, rightly so, as we shall see – to what this society would be like. Second, there is no agreed solution to «the problem of how a socialistic society could function» among socialists and communists, including those who call themselves “Marxists” 4

There is nowadays a way out of this difficulty. I will outline a criterion for analysing proposals for the kind of institutions a future socialist/communist/cooperative society 5 could have; a criterion that will enable us to retain only those proposals that prove capable of guiding not only the economy but also decision-making across all branches of government, in the traditional trifurcated sense of the term (executive, legislative, judicial). Let us call that criterion the beneficent principle (BP for short) just to anchor ideas.

2.Statement of the problem

How a socialist society could and should function?

3.The nature of the problem

The first question to ask is the nature of the problem to be solved — I mean, the problem of how a socialist society could and should function. The question is twofold. Is it a scientific problem or a technological problem? Is it a direct problem or an inverse problem?

— 3.1. Is it a scientific problem or a technological problem?

Technology is «that field of research and action that aims at the control or transformation of reality whether natural or social» (Bunge 2003:173).

Science and technology differ in that science «investigates the reality that is given», whereas technology «creates reality according to a design» (Skolimowski 1966:44). In other words, «science concerns itself with what is, technology with what is to be» (ibid.). Pure or basic science, if it is experimental – as particle physics or molecular biology, for example – also controls or transforms reality, but it does so only on a small scale and to know it, not as an end in itself. Whereas science brings about changes in reality to know it, technology knows reality to change it. In both cases, progress is at a premium. However, this progress is fundamentally different in the two cases, «science aims at enlarging our knowledge through devising better and better theories; technology aims at creating new artifacts through devising means of increasing effectiveness» (ibid., p.45) 6 .

Technology is «the design of things or processes [that is, in this case, artifacts] of possible practical value to some individuals or groups with the help of knowledge gained in basic or applied research. The things and processes in question need not be physical or chemical: they can also be biological or social. And the condition that the design make use of scientific knowledge distinguishes contemporary technology from technics, or the traditional arts and crafts. Our definition of “technology” makes room for all the action-oriented fields of knowledge as long as they employ some scientific knowledge» (Bunge 1988).

Hence, technology, in this view, subsumes the following fields: material, social, conceptual, and general. Pharmacology, industrial chemistry, electronics, communications engineering, computer engineering, and genetic engineering are examples of material technology. Management science, normative economy, law making, city planning, military science, and public policy studies are examples of social technology.

Social technology or sociotechnology is a «discipline that studies the ways of maintain, repair, improve or replace existing social systems and processes». To do that, it «designs or redesigns each other to deal with social problems» (Bunge 2012). Or, again, sociotechnology is the technology «involved in the design, assembly, maintenance, or reform of social organizations of all kinds, such as factories and government departments, schools and courts of law, hospitals and armies, and even entire societies in the cases of legislation and normative macroeconomics» (Bunge 1999).

Answer to question 3.1.

Clearly, our problem – how a socialist (/communist/cooperative) society could and should function – is a technological problem; a sociotechnological problem more specifically.

— 3.2. Is it a direct problem or an inverse problem?

A direct or forward problem is one whose research goes down either the logical sequence or the stream of events; that is, from premise(s) to conclusion(s), or from cause(s) to effect(s).

An inverse or backward problem is one whose research goes up either the logical sequence or the stream of events: that is, from conclusion to premise(s), or from effect to cause(s) (Bunge 2006).

In other words, work on direct problems is one of discovery, whereas the investigation of inverse problems calls for radical invention.

Here are some examples: «predicting phenotypic changes starting with natural selection, seedling emergence from physiological models, the presence of individuals at a given location starting with the theoretical population distribution, the manifestation of certain symptoms given a known illness, or the output of an artefact (e.g., be it a robot or a therapy) knowing the way the artefact works (e.g. the theory on which it is based), are all direct problems» (Marone 2020:5).

Inverse (or backward) problems are pervasive. «Think of diagnosing a sickness on the strength of its symptoms; of guessing a past event from its vestiges; of designing a device to perform certain functions; or of figuring out a plan of action to achieve certain goals. Likewise, to guess the intentions of a person from her behaviour; to discover the authors of a crime knowing the crime scene; to “image” an internal body part from the attenuation in intensity of an X-Ray beam (computed tomography); to identify a target from the acoustic or electromagnetic waves bouncing off it (sonar and radar); or to guess the premises of an argument from some of its conclusions (as in axiomatization) — all of these are inverse problems too. And all of them are far harder than the corresponding direct problems. In general, going downstream is easier than going upstream (Bunge 2006: 145).

Answer to question 3.2.

Clearly, our problem is an inverse problem. It consists of figuring out a detailed plan of action to achieve certain attainable goals – in our case, the goal is to institute an all-round socialist society – as opposed to describing any such society (which would be impossible because they do not yet exist).

4.Technological prerequisites of socialism

Global cooperativism or socialism or communism (again, I am using these words interchangeably) as a mode of production beyond global capitalism requires a definite stage of development of technology. Denying it is incompatible with a materialistic and scientific point of view. In Marx’s time this stage had not been reached. Nor had it been reached for most of the Soviet Union’s lifetime. It was only reached in the last decade of the 20th century (Cockshott 2017) – at a time, therefore, when the Soviet Union and its subordinate Eastern European block had already been dissolved [1989-1991] – with the synergetic convergence of several technologies:

# Barcodes (which allow tracking all purchases and sales in real time, as well as efficiently effecting management and control of stock inventory).

# Electronic debit cards (which allow replacement of cash with non-transferable labour credits).

# Internet, including the WWW and the Internet of Things 7 (which allows real-time cybernetic planning and can solve the problem of dispersed information – Hayek’s key objection). 8

# Smartphones (which allow universal electronic voting any time on all relevant issues).

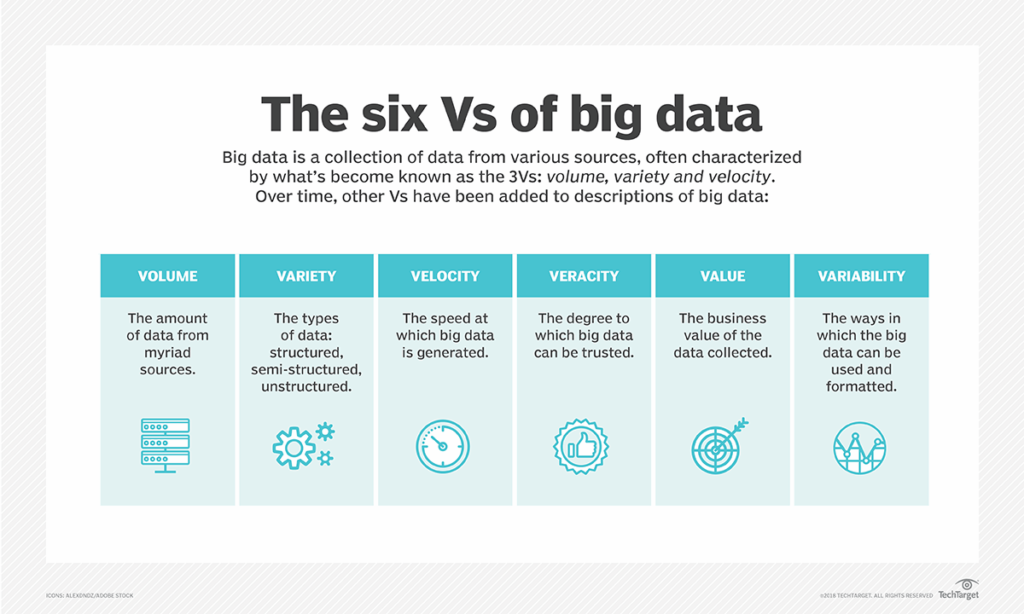

# Big Data (which allows concentration of the huge volume of information needed for planning) 9

# Supercomputers (which can solve in seconds the millions of equations that need to be solved in planning for a technologically advanced economy and which make it possible economic calculation in terms of labour time – Mises’ key objection 10).

These technologies, 11 which empower and boost industry (especially machine industry), telecommunications and agriculture to levels of productivity and efficiency that no-one could foresee at the time of the First, Second, or Third International 12, are, nonetheless, necessary to implement some of the distinctive features (I have signalled them with an asterisk [*]) of Marx’s first or lower stage of communism:

— No private owners of the social means of production, *no money, *no commodities, *no exchange of products, *no hired labourers, *economic calculation in terms of labour time and use values, *payment in labour time credits according to personal worktime accomplished, public services paid for by an income tax on labour incomes (Marx 1875).

The features with an asterisk are not out of reach anymore, but just the opposite, because there are already available the technologies required for their implementation. The basic material prerequisite of a working socialist society (a technological prerequisite) is something that can be achieved not in the distant future but right now, today, in the most developed capitalist countries — those within the European Economic Area [which includes all 27 European Union Member-States as well as the four members of EFTA], United Kingdom, Russia, USA, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, China, Taiwan, and Singapore. 13.

Now, that we know that our problem is an inverse sociotechnological problem let us then restate it.

5. Restatement of the problem

How a socialist/communist/cooperative society could and should function, so that «the present [exploitative], pauperising, and despotic system of the subordination of labour to capital can be superseded by the republican and beneficent system of the association of free and equal producers», «to convert social production into one large and harmonious system of free and cooperative labour» (Marx 1867).

6.The technological criterion for designing a socialist society

Stated in general, sociotechnological terms, the solution to this problem is as follows:

Design an institutional system of socialism that will meet such and such specifications. The specifications list the essential functions or tasks that the system is expected to perform.

I call this general goal-statement the technological criterion for designing a socialist society. The beneficent principle is a concretization of the technological criterion.

7.The beneficent principle

Specification 1: Convert private firms producing consumer goods into labour-managed production cooperatives. 14

Specification 2: Convert market and non-market Services of General Economic Interest (SGEI) – energy, roads, railways, ports, airports, postal services, telecommunications, machine industry – and Social Services of General Interest (SSGI) – water supply, electricity supply, sewerage, kindergarten, schools, universities, polytechnics, healthcare, social security, fire services, rescue services, etc.– into public consortia run by workers and users 15.

Specification 3: Develop centralised internet system to track all purchases and sales.

Specification 4: Use supercomputers, personal computers, barcodes, big data, and the internet – which allow real-time cybernetic coordination and planning – to efficiently plan and coordinate economic activity in terms of natural units and labour time without recourse to the intermediary of money or markets.

Specification 5: Price consumer goods in labour hours at transfer-clearing levels 16 and use cybernetic feedback from sales and the discrepancies between these prices and the values of the goods to determine the optimal level of production and adjust output to consumer preferences.

Specification 6: Withdraw all paper money and coins and replace them with electronic payment (debit) cards.

Specification 7: Develop a system of remuneration based on labour time with non-transferable labour time credits allocated via electronic debit cards.17

Specification 8: Fund the surplus product by levying a poll tax (a tax determined as a uniform, fixed amount per individual) on all workers, approved by referendum. The working population will decide on the level of the tax by vote every year. A multiple-choice ballot could allow the people to decide, for instance, between more such and such kind of SSGI or more consumption, between more environmental protection or more funding for the arts. Only when the surplus product is provided voluntarily, and its collective appropriation is under the management and control of its producers, does it cease to be exploitation.

Specification 9: Harness computer networks and mobile smartphone voting to allow direct democratic control by the mass of the population over the planned economy 18.

As it was already mentioned, this allows major strategic decisions to be taken democratically every year, questions like: How much labour to devote to education? How much to healthcare, pensions, social security? How much to environmental protection? How much to scientific and technological research? How much to the arts? How much to new investment?

Specification 10: Develop a democratic constitutional program, based upon the right of political initiative by the citizens in all matters 19 and the sovereign control of its collective body over all appointees in executive and administrative councils, law courts, planning departments, audit institutions as well as over the military commanders and the superintendents of police.

10.1. The sovereignty of the collective body of citizens should not be delegated to an elected chamber (or chambers) of professional politicians and/or to an elected president, as in the political systems that currently label themselves democracies or liberal democracies. This is a misnomer. They are all electoral oligarchies, elective liberal oligarchies. Democracy is a system of government of the people, by the people, for the people, in that each citizen has an equal share/chance in ruling and being ruled. Electoral oligarchy, on the other hand, is a system of government of elected professional politicians and assorted magistrates co-opted by the former. When it coexists with a broad spectrum of constitutional rights (including labour rights), freedoms and guarantees won during centuries-long emancipatory struggles that continue to be fought, it can be called liberal oligarchy. The fact that liberal oligarchy (or even electoral oligarchy) can still get away with calling itself democracy is one of the most remarkable confidence tricks in history (Cottrell & Cockshott 2003:15).

10.2. Elections (selection of officials/magistrates by ballot) are both oligarchic and aristocratic, not democratic. They are oligarchic because only a “few people,” the oligoi, have the chance of being elected. And they are aristocratic because they introduce the element of deliberate choice, of selection of the “best people,” the aristoi, the elite, in place of government by all the people. In a class-divided society the “best people” are always the better off, be they the wealthiest, the most ruthless, the most well-spoken, those who have inside information or some combination of the above. We do not know who could be the aristoi in a classless society. But we know, ever since Aristotle, more than 2350 years ago, that elections are always an oligarchic-aristocratic device, whereas appointment from all by lot (or roster) is always a democratic device (e.g., Politics 1273a, 1273b, 1294b, 1300b). This is because, by adopting the democratic principle that magistrates (i.e., citizens holding an office of public authority) are selected from all by lot (or roster) and for a collegial body (council, jury, neighbourhood watch patrol, and the like), anyone might be called to serve and everyone is certain to learn by doing, with the help of each other, thus producing a highly politicised population.

Consequently, elections by ballot should be confined to ambassadors, members of the supreme audit institution (SAI) 20, and high-ranking commissioned officers (generals, superintendents of police, and the like), since these are offices requiring expert knowledge and whose holders are quite often left to their own devices as a matter of course. Therefore, they should be elected from a short list of candidates previously selected by public contest.

10.3. There will be no government responsible to parliament, congress, or head of State (president or monarch), as is currently the case in electoral oligarchies, whether liberal or illiberal, for there will be no State 21 (see 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7 and 10.8).

10.4. Instead, the day to day running of the socialist democracy should be entrusted to a general council of magistrates periodically drawn by lot from the collective body of citizens for a short and non-renewable term of office. The general council has no legislative powers and is responsible merely for preparing the legislation to be voted by the people, for enacting the policies decided upon by the people, and for electing, supervising, and dismissing the ambassadors, members of the SAI, and the high-ranking commissioned officers in the citizen militia and the citizen police (see 10.6 and 10.7 below).

10.5. The same holds true for the law courts. There will be neither professional judges nor professional public persecutors. As in ancient Athens of the 5th and 4th centuries B.C., the courts shall be constituted by panels of magistrates chosen by lot from the collective body of the citizens above the age of 25 or 30 without a criminal record, for a specific lawsuit. They shall act as both judge and jury chaired by foreperson of panel, with the help of lawyers (who will not have the right to vote). Their decisions shall be taken by secret ballot.

10.6. The salaried, professional police will be abolished, with two exceptions: forensic services and detective services. Law enforcement and public safety will be by a citizen police. There will be an obligation on all healthy citizens without a criminal record to serve in the police X days per year. Citizens on police duty would have the right to carry and bear arms when required (for instance, in self-defence, to avoid a murder, or to arrest an armed criminal). Police duty is to be made by roster in one’s own neighbourhood. Exemptions for those over a certain age (say, 50 years old), pregnant women, mothers in the nannying period, the disabled, etc. Professional forensic services and a small professional detective corps will be retained to investigate smarter crime. Detectives would not be armed, unless arrests must be made, and these will be done under the superintendence and with the help of the citizen police or the citizen militia (see below).

10.7. The standing army will be abolished and replaced by a citizen militia. There will be an obligation on all able-bodied youngsters aged 18-22 to receive military training during a brief period (say, 3 months) in the citizen militia. When their period of service in the militia has ended, the militia’s reservists (say, until 34 years old) would have the right of keeping their rifles and fifty rounds of ammunition at home, as is the case in Switzerland. A small professional corps of military experts will be retained to serve as warrant officers — military trainers of the members of the militia, advisors, general staff, and technicians (aircraft pilots, naval pilots, computer engineers, etc.).

10.8. All appointments of magistrates should be limited to a very short time (say, from one week to one year, depending on the case) or at least as many as possible; and none should be in the same office twice in a row, or even twice during his/her lifetime, or very few, and very seldom, except for the citizen police (for the reason given in 10.6) and for high-ranking commanders of the citizen militia (but only in the event of war). 22 Payment for hours spent on public duty should be made equal for all, at current rates of “wages.”

8. Conclusion

The first or lower phase of the communist society – Marx wrote in 1875 – will only emerge «after prolonged birth pangs from the capitalist society». Marx was right. With hindsight, we can say that the technological prerequisites of the first phase of the communist society took about 115 years to emerge from the capitalist society since the days he penned his Critique of the Gotha Program.

This is the reason the solution I have laid down here to the problem of how a socialist/communist/cooperative society could and should function in its first or lower stage is anything but “utopian,” in both senses of the term as is usually employed in political science — viz. (i) something which cannot be achieved nowhere, and (ii) something too perfect to be possible. 23

Accordingly and not surprisingly, this solution – which I have called the Beneficent Principle of socialist/communist/cooperative societies for mnemonic purposes – has nothing resembling the “utopian” proposals published by some socialists who lived before Karl Marx (Thomas More, Robert Owen and the like), and the blueprints for the forthcoming socialist society published by the leaders of the Second International (1889 –1914) and the Third International (1919–1943) — such as August Bebel and Karl Kautsky in Germany, Jean Jaurès and Émile Vandervelde in the French-speaking labour movement, Nikolai Bukharin, Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin in Russia, or Antonio Gramsci in Italy.

The former did not know (and could not know) that there are quite strict technological prerequisites (along with economical and political ones) for a socialist/communist/ cooperative society to function and thrive, whereas the latter ignored or misinterpreted Marx’s outline of the lower and higher phases of communism, in which those prerequisites are succinctly but clearly described (Marx 1875). Consequently, they have little analytical value for contemporary social reality.

A single example may suffice. Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), founding member and one-time leader of the Communist Party of Italy, wrote in November 1917:

The Russian proletariat, educated in Socialism, will start its history from a high level of production that England has only got to today; its starting point will be something which has been accomplished elsewhere, and from this accomplishment it will be driven to reach the economic maturity that Marx sees a necessary for collectivism.

Revolutionaries will themselves create the conditions needed for a full and complete fulfilment of their ideal and they will do so in less time than capitalism would have. Socialist criticisms of the bourgeois system, which highlight its shortcomings and the unequal distribution of wealth, will enable revolutionaries to do better, to avoid such shortcomings themselves, to not fall into the same traps. In the beginning it will be a collectivism based on misery, on suffering. But it would have been these very conditions of misery and suffering which would have been inherited from a Bourgeois regime.

This amounts to saying that (a) there are no technological prerequisites to socialism; that (b) the first phase of socialism can be one of misery and suffering; that (c) a small group of a few tens or hundreds of thousands of individuals (such as the Bolsheviks) can create the economic conditions necessary for socialism, including the numerical growth of the proletariat to become the majority of the population in the world largest country by far –1/6 of the land surface of the Earth, stretched across two continents, spanning 11 time zones, incorporating a great range of environments and landforms, and including approximately 145 million people at the time, mostly peasants, with around 130 languages spoken natively –, and (d) it may even succeed in doing so in less time and/or with less suffering than have historically been spent by the capitalist class and its managers in achieving it.

Of course, all this ignores the conclusions reached by Karl Marx during his mature years (1856-1883). This is not chance. Gramsci was keenly aware of it. In the same article he said approvingly:

The Bolshevik revolution is based more on ideology than actual events (therefore, at the end of the day, we really do not need to know any more than we know already). It is a revolution against Karl Marx’s Capital. In Russia, Marx’s Capital was the book of the bourgeoisie, more than of the proletariat. It was the crucial proof needed to show that, in Russia, there had to be a bourgeoisie, there had to be a capitalist era, there had to be a Western style of progression, before the proletariat could even think about making a comeback, about their class demands, about revolution. The Bolsheviks renounce Karl Marx and they assert, through their clear statement of action, through what they have achieved, that the laws of historical materialism are not as set in stone, as one may think, or one may have thought previously [emphasis added by me].

Gramsci did not live long enough to see whether his prophecies were successful. We have the privilege of knowing the answer, and the answer was not what he expected. This is not surprising. When we analyse their content in theoretical terms, we find that it is not only not right; it is not even wrong.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Source: Edited version of a presentation at 11th annual conference of International Initiative for Promoting Political Economy (IIPPE), September 13, 2021.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

References

Angenot, Marc (2000), “Society After the Revolution: The Blueprints for the Forthcoming Socialist Society published by the Leaders of the Second International”. In Learning from other Worlds. Edited by Patrick Parrinder. Liverpool. Liverpool University Press.

Aristotle (335–323 B.C.?), Politics. Translated by Carnes Lord. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013, second edition.

Bellamy, Edward (1887), Looking Backward: 2000–1887. Boston: Ticknor and Co., 1888. First edition; E-book Project Guttenberg, 2008. https://www.gutenberg.org/ ebooks/624

Bernardo, João (2021), “O Futuro Fugiu. 2”. Passa Palavra.30-09-2021. https://passapalavra.info/2021/09/ 139867/

Bunge, Mario (1988), “The Nature of Applied Science and Technology”. In Scientific Realism: Selected Essays of Mario Bunge. New York: Prometheus Books, 2001.

Bunge, Mario (1999), “The Technology-Science-Philosophy Triangle in its Social Context.” In Scientific Realism: Selected Essays of Mario Bunge. New York: Prometheus Books, 2001.

Bunge, Mario (2003), “Philosophical Inputs and Outputs of Technology”. In Philosophy of Technology. The Technological Condition. Scharff, Robert Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

Bunge, Mario (2006), Chasing Reality: Strife over Realism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press Incorporated.

Bunge, Mario (2012), Las Ciencias Sociales en Discusión. Buenos Aires: Random House Mondadori S.A. Title of the English edition: Social Science under Debate.

Cockshott, W. Paul (2007), “Mises, Kantorovich and Economic Computation”. MPRA. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. MPRA Paper No. 6063. Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/6063/

Cockshott, W. Paul (2017), “Big Data and Super-Computers: Foundations of Cyber Communism”. Paul Cockshott Blog, July 24, 2017.

Cockshott, W. Paul (2020). “The US Crisis.” Paul Cockshott Blog. June 18, 2020.

Cockshott, W. Paul & Karen Renaud (2007), “Electronic Plebiscites”. In: MeTTeG07, 27-28 September 2007, Camerino.

Cockshot, W. Paul & Karen Renauld (2010), “Extending Handivote to Handle Digital Economic Decisions”, Proceedings of ACM-BCS Visions of Computer Science. 2010.

Cottrell, Allin & W. Paul Cockshott (1993), Towards a new socialism. England: Spokesman, Bertrand Russell House, Gamble Street, Nottingham.

Cottrell, Allin & W. Paul Cockshott (1997), “Information and Economics: A Critique of Hayek”. Research in Political Economy, vol. 16, 1997, pp. 177-202.

Cottrell, Allin & W. Paul Cockshott (2003), “Computers and Economic Democracy”. Revista de Economía Institucional. vol.1 no.se Bogotá 2008.

Cottrell, Allin & W. Paul Cockshott (2007), “Against Hayek”. MPRA. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. MPRA Paper No. 6062. Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/6062/

Gramsci, Antonio (1917), “The Revolution against «Capital»”. First published Avanti! 24 December 1917. Translated by Natalie Campbell. https://www.marxists.org/archive/gramsci/1917/12/revolution-against-capital.htm.

Jossa, Bruno (2012), “Cooperative Firms as a New Mode of Production”. Review of Political Economy, Volume 24, Issue 3.

Keynes, John Maynard (1935), The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Rendered into HTML on Wednesday April 16 09:46:33 CST 2003, by Steve Thomas for The University of Adelaide Library Electronic Texts Collection.

Magni-Berton, Raul & Clara Egger (2019), RIC : Le référendum d’initiative citoyenne expliqué à tous : Au cœur de la démocratie directe. Limoges, FYP éditions, coll. « Présence/Questions de société ».

Marone, Luis (2020), “On the Kinds of Problems Tackled by Science, Technology, and Professions: Building Foundations of Science Policy”. Metascience, no.1, Mario Bunge: Thinker of Materiality.

Marx, Karl (1867), “Instructions for the Delegates of the Provisional General Council. The Different questions.” In Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, Collected Works, vol.20. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2010, p.190.

Marx, Karl (1875), Critique of the Gotha Program. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/

Mises, Ludwig von (1922, 1932, 1936, 1951), Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis. trans. J. Kahane. Foreword by F.A. Hayek. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1981.

Reinsel, David, Gantz, John & John Rydning (2018), The Digitization of the World From Edge to Core. An IDC White Paper – # US44413318, Sponsored by Seagate.

SAS (2021), Internet of Things (IoT). What it is and why it matters. https://www.sas.com/en_us/company-information.html

Scarano, Eduard (2020), “The Inverse Approach to Technologies”. Metascience, no.1, Mario Bunge: Thinker of Materiality.

Skolimowski, Henryk (1966), “The Structure of Thinking in Technology”. Technology and Culture, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Summer, 1966).

Zachariah, David (2007), “Democracy without Politicians”. In Arguments for Socialism, by Paul Cockshott & David Zachariah. E-book © the authors.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

[*] José Catarino Soares is a Portuguese linguist living in Lisbon, Portugal. He holds a PhD in linguistics from the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris. He has taught and researched for almost three decades in higher polytechnic education in Portugal, where he was a coordinating professor. Before devoting himself to linguistics, his main and favourite area of research, he taught sociology, where he also holds a degree. Today, he is an independent researcher.

[*] José Catarino Soares is a Portuguese linguist living in Lisbon, Portugal. He holds a PhD in linguistics from the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris. He has taught and researched for almost three decades in higher polytechnic education in Portugal, where he was a coordinating professor. Before devoting himself to linguistics, his main and favourite area of research, he taught sociology, where he also holds a degree. Today, he is an independent researcher.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Notes

- «The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back». J-M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (last page)

- The SAPD was renamed the Social-Democratic Party of Germany [Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD] in 1890.

- «The European socialist movement under the Second International (1889–1914) officially designed an abundance of detailed blueprints and precise visions of the post-revolutionary society. For the most part these tableaux were components of the day-to-day propaganda that accompanied social struggles, as articles in party newspapers and pamphlets. One cannot criticize the evils of capitalism, one cannot show how this economic system is the ‘unique cause’ of poverty, alcoholism, or prostitution without showing how and why the proletarian revolution will automatically eradicate these evils. One thus finds a multitude of sketchy glimpses of the ‘collectivist’ social order contrasted with the descriptions of capitalism and its evils. On the other hand, there is also a large number of full-scale books which dealt exclusively with the systematic description of the socialist vision of the future.» (Angenot 2000). This tendency continued under the Third International (1921-1943), though it was polarised during this period by the theoretical debates and practical problems raised by the huge transformations of the Russian economy under the aegis of the Soviet Union.

- In fact, the situation is even more murky. «Communism, as it was understood when the word was coined, no longer matters to those who claim to be its defenders today» (Bernardo 2021). Bernardo refers here, in the first place, to the communist parties. For these parties, communism was never synonymous with the «republican and beneficent system of association of free and equal producers» (K. Marx, in Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, Collected Works, vol.20. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2010, p.190) — and therefore a classless and Stateless society. It was, instead, synonymous with the nationalisation of the economy and its control by the State, the State being in turn led by the communist party as the sole and supreme holder of explicit power in all areas of social life. The same holds true for the word “socialism” and most of the parties that name themselves with it. The title of this article should be read with this warning in mind.

- It is perhaps useful to note that I am not innovating when I declare the synonymy between these three concepts. Instead, I follow in the footsteps of Karl Marx who was, if I am not mistaken, the first author to do so in many places in his written work.

- «The results of technological designs are artifacts that constitute a new level of reality, the artificial level, which is built with the aid of the natural level but different since it arises from the purposes of the human being — if this or other rational beings did not propose objectives, there would be no artifact» (Scarano 2020:5).

- The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to a vast number of artifacts that are connected to the Internet so they can share data with other things – IoT applications, connected devices, industrial machines and more. Internet-connected devices use built-in sensors to collect data and, in some cases, act on it. Real-world IoT examples range from a smart home that automatically adjusts heating and lighting to a smart factory that monitors industrial machines to look for problems, then automatically adjusts to avoid failures. «Today, we are living in a world where there are more IoT connected devices than humans.» (SAS 2021).

- Cottrell & Cockshott 1997, 2007.

- International Data Corporation (IDC) predicts the world’s digital data will grow to 175 zettabytes in 2025. One zettabyte is equivalent to a trillion gigabytes. If you were able to store the entire Global Datasphere on DVDs, then you would have a stack of DVDs that could get you to the moon 23 times or circle Earth 222 times. If you could download the entire 2025 Global Datasphere at an average of 25 Mb/s, today’s average connection speed across the United States, then it would take one person 1.8 billion years to do it, or if every person in the world could help and never rest, then you could get it done in 81 days (Reinsel, Gantz & John Rydning, 2018).

- Cockshott 2007.

- I did not include thermonuclear fusion (which will provide a clean, safe, and unlimited source of energy) because the main technology needed to produce it, the tokamak – a device which uses a powerful magnetic field to confine plasma in the shape of a torus – was invented in the late 1950s in the former Soviet Union. The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), the largest tokamak in the world, which began construction in 2013 in France, near Aix-en-Provence, is projected to begin full operation in 2035. It is intended as a demonstration that a practical fusion reactor is possible.

- With one great exception, Edward Bellamy (1850-1899), who invented the idea of the credit card, based on the recently invented Hollerith punched cards.

- There are two other material prerequisites of socialism. One is economic and unfolds in two distinct parts: a negative part and a positive part. The negative part is the growing accumulation of capital worldwide and its consequences and limits in the valorisation process of capital — the periodic expansions and contractions (recessions and depressions) of the business cycle under capitalism. The positive part is the development, by the very economical agencies of capitalism, of (i) a class of wage-workers who often form the majority of the population of their native or adopted countries, and of (ii) the technologies designed to make their social work more productive and efficient. There is another material prerequisite of socialism – a political prerequisite this time – without which the technological prerequisite cannot be actually fullfilled. I mean the existence of wage-working classes that are willing to join forces and determined to break free from the shackles of capitalism, both in the workplace and in the wider socio-political sphere, on a national and international scale. Note that the converse is also true. The political prerequisite of socialism can be fulfilled without the technological prerequisite being fulfilled. In that case, socialism is not possible either. The institution of socialism requires the synchronised conjugation of both. But this is not the topic of this paper. Note also that the economic prerequisite is the material basis of the political prerequisite. The insufficient and negative valorisation of accumulated capital is the major process that periodically blocks or damages the capitalist mechanism from the inside. This in turn may well encourage the wage-working classes (which are constantly engaged in a Sisyphean struggle, sometimes covert and sometimes overt, against exploitation) to set free the elements of the new society, both economical and technological, with which old capitalist society is pregnant. However, this is not the subject of this paper either. Suffice it to say here that also in these two respects the new society is born from the womb of the old one.

- In a labour-managed production cooperative, (a) all decisions about production, working time, and the work process are taken either directly by a vote of all the workers, or by councils periodically appointed by them by lot, roster, election or a combination of all these procedures; (b) the cooperative finances its investments with borrowed funds only; (c) the cooperative delivers its total product – intended to serve as an intermediate medium or end product for consumption or production – to the community shops, storehouses and warehouses, and receives back from the common funds of the global cooperative society whatever is necessary to cover its (re)production costs, the administration costs not pertaining to production, and the general deductions for the social security that correspond to its individual workers; (d) each worker receives from the cooperative a certificate, on an electronic card credit, that he/she has provided such and such number of working hours, and with that card (after deducting his/her tax for the common funds of the global cooperative society) he/she purchases in the community shops consumer goods as much as the same amount of labor cost. Thus, «[t]he same amount of labor which he/she has given to society in one form, he/she receives back in another» (Marx 1875). Clauses (b) and (c) rule out two major shortcomings of co-operatives that self-finance their investments — namely underinvestment and the tendency of majority members to oust minority members in an attempt to appropriate earnings on previous investments (Jossa 2012).

- «For example, a local council administering a hospital could be made up by a random sample of residents and workers at the hospital. The appointees in the national health care council could be drawn by the same principle or by a random sample from a pool of candidates elected by the local councils. In any case, their term of service is limited. They are economically compensated for loss of work and subject to recall» (Zachariah 2007).

- «Market-clearing prices [It would be better to call them “transfer-clearing prices” to avoid confusion with the market as it is ordinarily understood, E.N.] are prices which balance the supply of goods (previously decided upon when the plan is formulated) and the demand. By definition, these prices avoid manifest shortages and surpluses. The appearance of a shortage (excess demand) will result in a rise in price which will cause consumers to reduce their consumption of the good in question. The available supply will then go to those who are willing to pay the most. The appearance of a surplus will result in a fall in price, encouraging consumers to increase their demands for the item» (Cottrell & Cockshott 1993:98). E.N. = editorial note.

- That is, a system that allows every worker to receive an electronic credit in individual means of consumption proportional to the labour hours he/she has supplied.

- W. Paul Cockshott and Karen Renaud (2007, 2010) have successfully developed one such system, called Handivote.

- Citizens’ political initiative is a means by which a proposition is signed by a sufficient number of registered voters within a given time period, and then is put to a plebiscite or referendum, in what is called a citizen-initiated referendum (CIR). As conceived here, a CIR in all matters should be applicable to four types of procedures: 1) the legislative referendum, which would consist in submitting a bill to the people; 2) the abrogatory referendum, which would consist of the possibility for the population to repeal a law previously adopted; 3) the recall referendum, which would consist in dismissing a magistrate before the end of his term of office; 4) the constitutional referendum, which would consist in allowing the people to amend the country’s Constitution (for details, see Magni-Berton & Eger 2019). Issues of public interest «could be debated by randomly drawn citizens and experts on national television and then voted electronically by the viewers. Public internet servers could be set up to channelise public opinion; issues are brought up, if they gather sufficient signatures, they are subject to referendums. This would be a modern Assembly» (Zachariah 2007).

- A supreme audit institution (SAI) is responsible for overseeing and holding all collective bodies of socialist democracy (general council, planning departments, administrative councils of SGEI and SSGI, citizen militia, citizen police, law court juries, etc.) account for their use of public resources. Where there is more than one audit institution fulfilling the oversight of public expenditure, the SAI would be distinguished as possessing the strongest constitutional guarantees of independence.

- By “State” I mean the pyramidal apparatus of special institutions of decision-making, coercion, repression and destruction that (A) have a monopoly of (i) explicit economic power (e.g., administration boards of private and State-owned enterprises), (ii) explicit political power (elected or self-appointed heads of State, government officials and legislators; courts in the hands of professional judges and prosecutors), and (iii) a legal monopoly on the use of weapons of war (police and military forces) inside and sometimes outside (e.g., NATO) the borders of a country, and that (B) are separated from the collective body of citizens by multiple layers of institutional isolation.

- Let me add, just to make everything clear, that the existence of (i) ambassadors and (ii) citizen militias are only justified as long as there are States – and therefore economically and politically organised capitalism – in this or that part of the world which may pose an actual or potential military threat to socialist/communist countries. The extinction of (i) and (ii) for having become useless and obsolete will then be one of the most unequivocal signs that we will have entered the second or higher phase of communism/socialism.

- Utopia means “no-where,” “no place”. The word has been used – against the original intention of its creator (Thomas More) – to mean a perfect society, an idyllic but impractical one. For More, on the contrary, utopia was a place–where–we–are–happy, a model of social happiness. It was the benign character of the institutions of his imaginary island of Utopia that justified its name, not its perfection. However, it was the pejorative understanding of “utopia,” that of an idyllic but impractical society, that eventually prevailed among the reading public. Accordingly, utopianism or utopism is usually interpreted as being any model of a perfect society put into practice. Some say that this is where the trouble begins because imperfect humans can never achieve perfectibility. Consequently, utopianism or utopism – so the argument goes – would lead inevitably to a collective nightmare becoming real. However, the advocates of this argument never bother to tell us what they mean by perfection, which is why the alleged associations between perfection and misfortune cannot be taken seriously.